A Life-Saving Spray – Community Groups Come Together to Offer Narcan Training

When a person who abuses opioids experiences an overdose, the difference between life and death is a matter of minutes.

That’s why four community organizations have joined together to educate the public on Narcan, a highly effective and easy-to-use form of naloxone, an overdose antidote.

Narcan works fast and is as easy to use as nasal spray. Training family and friends on how to use the antidote makes them effective allies in opioid overdose prevention.

Through a United Way grant, Tapestry Health, Gándara Center, and the Hampden County Addiction Task Force conducted a series of six Narcan trainings (four in English and two in Spanish) this fall as part of their overdose-prevention efforts. The sessions, titled “You Nar-Can Save Lives,” explained what Narcan is and how to properly use it. The training sessions also addressed topics such as how to detect an overdose and the proper way to administer rescue breathing, a technique similar to CPR. Everyone who attended was provided with a kit consisting of two doses of Narcan and instructions on its use.

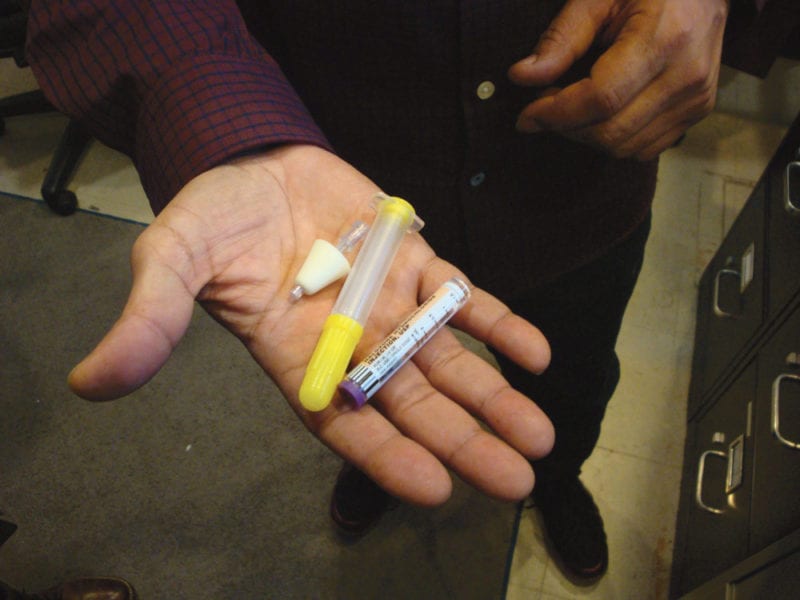

While naloxone has been in use for more than 20 years, earlier methods of administering it required several steps, such as putting together a nasal syringe and a 4-mg vial of naloxone. Proper dosing required spraying 2 mg in one nostril and 2 mg in the other. Because of its complexity, the Massachusetts Department of Public Health (DPH) does not recommend use of this syringe by a layperson.

By contrast, Narcan is a simple-to-use, single-dose dispenser containing 4 mg of naloxone and requires only one spray into one nostril.

Pedro Alvarez, syringe access program manager at Tapestry Health, said that, when trying to revive someone with the older nasal syringe, any careless handing could result in losing some or all of the dosage or even shattering the glass vial that holds the naloxone.

“Narcan delivers a more concentrated dose, and it’s much easier to use,” he explained.

In 2015, legislation filed by state Sen. Eric Lesser helped create the Municipal Naloxone Bulk Purchasing Trust Fund to provide first responders across Massachusetts with affordable access to Narcan. Initially, the bulk price was $40 for a two-dose package. This year, the price increased to $71 per package, with full retail costing around $125.

Lesser has said publicly that first responders’ access to Narcan has contributed to a decrease in opioid-overdose deaths. According to the DPH, in 2017, there were 2069 opioid-overdose deaths, a decrease of 4{06cf2b9696b159f874511d23dbc893eb1ac83014175ed30550cfff22781411e5} from 2016, when the total reached a record 2,154 opioid-overdose deaths.

Lisa Brecher, director of Marketing and Development for Gándara Center, noted that, while it’s important for first responders to be trained and to carry Narcan, they may not always reach those who need it most.

“Because of strained relationships in the past with police, the populations we serve are less likely to call on first responders if they encounter an overdose situation,” she said.

In an attempt to change that attitude, police officers from Holyoke and Springfield addressed the two Spanish-language training sessions held in those cities. At both, police officers urged community members to call them in an overdose situation.

“The officers emphasized that their one role in an overdose situation is to save a life,” Brecher told HCN. “They assured people that they would not search anyone present for a warrant. It was a very powerful statement.”

For this issue and its focus on addiction, HCN takes an in-depth look at the training program and how it makes a life-saving medication far more accessible.

Dose of Reality

Alvarez said his staff counsels community members on the importance of making a 911 emergency call even if they revive someone with Narcan, because the individual who overdosed might have fallen or have other issues that need additional medical attention.

That’s an example of how in-depth the training regarding Narcan has become, and why it’s important to cover all the bases when it comes to overdoses and responses to them.

Indeed, a dose of Narcan usually takes two to three minutes to travel through the nose and into the brain in order to work; Alvarez said an untrained person might panic and give more Narcan before the first dose has a chance to work.

“If somebody is responding to an overdose, two to three minutes can feel like two to three hours,” he said. “This [giving more of the drug] will not make the Narcan work faster, but may cause more severe withdrawal symptoms.”

It’s also important to call first responders, because someone overdosing on a synthetic opioid like fentanyl often needs a second or third dose of Narcan to reverse the overdose. Alvarez said the person can also fall back into an overdose up to 30 minutes after they are revived.

Alvarez shared with HCN an illustration of the granular amounts of different opioids that could trigger an overdose. Resembling the size of salt grains, it would take about 100 grains of heroin to trigger an overdose, while only 20 grains of fentanyl would lead to an overdose.

Alvarez said there is growing concern about carfentanil, a new opioid finding its way into street drug supplies. According to RecoveryFirst.org, carfentanil is 100 times more potent than fentanyl and is not approved for use by humans in any capacity.

The website said carfentanil is used to sedate large animals, primarily elephants. Using the salt-grain comparison again, a single grain of carfentanil could trigger an overdose.

Community groups face a two-front battle against more potent opioids and a lesser-known but equally challenging battle involving the stigma of being or having a family member with opioid abuse issues. Trainers at the sessions urged family and friends to begin having conversations with the person using opioids and making Narcan part of the discussion so they understand that this life-saving resource is available.

“A lot of overdoses are happening because people take these drugs alone; they feel the stigma of being an opioid user, so they usually hide somewhere like a locked bathroom or out in the woods,” Alvarez explained. “We tell them, ‘let people know if you’re going to use alone. Make sure someone in the house knows where to find the Narcan, or leave it out in plain sight so, if you overdose, a family member can immediately respond.’

“That’s a tough conversation to have,” he went on, “but it can go a long way to saving a life.”

Alvarez pointed out that Narcan is a life saver, but it is not a cure. Narcan will keep a person alive until they decide to treat their addiction.

“Some people experience an overdose, and it scares them straight. Others still use but are more careful, and then there are some who will just keep using and experiencing overdoses,” Alvarez said, adding that, when a person gets to the point of ‘I’m done with this [opioid use],’ peer-based services are an effective way to promote lasting change.”

After someone is saved by Narcan, Brecher said, the most important work is connecting the person to the next step of treatment.

“One thing that’s really lovely in the recovery community is the sense of giving back,” she said. “It’s easy to find someone who is willing to be a peer now that they are in recovery. They feel they’ve reached a good place through the support of others, and now they want to reciprocate that support.”

She said peer-support services work because the person seeking recovery is interacting with someone who looks like them, talks like them, has kids like them, and lives in the same neighborhood as them. “A common reaction from those in treatment is, ‘wow, I can’t believe opioid abuse has affected this person and their family, too.’”

For some people, Brecher said, true recovery occurs only after several relapses. “We know that people try to get help multiple times before they’re successful. It’s like that with any addiction. If you were a smoker, you might have tried to quit eight or 10 times before it actually stuck.”

Both Alvarez and Brecher said there are misperceptions about who uses opioids, which only adds to the stigma. Brecher noted that it’s easy to assume that a low-income family member with a substance-abuse issue started on the street using, but that’s not necessarily true.

“Many of the people we talk to had back surgery or were involved in a car accident; their addiction started with prescription opioids to manage pain,” she said, adding that, because prescription pain medication is perceived differently than heroin, family members might not easily recognize the potential for abuse and overdosing.

Meanwhile, many prescriptions for pain medication are accompanied by a prescription for Narcan. Alvarez noted that, while Narcan is available through private insurance with a co-pay, some individuals are reluctant to obtain Narcan from the pharmacist, where it will show up on their insurance claims. Instead, they go to Tapestry for it.

“Drug abuse doesn’t discriminate among rich, poor, white, black, young or old,” he said. “We treat everybody who walks through the door with the same dignity.”

Bottom Line

According to Brecher, reaching out to people, even with a life-saving message, requires more strategy now than in the past.

“At one time, organizations could purchase a billboard ad or run a public awareness campaign. We’re trying a more boots-on-the-ground approach to reach people where they are.”

In addition to taking part in community Narcan events, Brecher said Gándara Center serves a large part of the Latino community, where attending church is a strong part of the culture. As a result, places of worship are becoming important forums to address the stigma of opioid use and abuse. Pastors from several denominations in the Latino community are joining the fight and requesting training sessions for their congregations.

“When a pastor who is respected and trusted by church members delivers the message,” he noted, “it’s very powerful and diminishes the ugliness of the stigma.”

Alvarez said everyone knows someone — or knows someone who knows someone — affected by the opioid crisis, and Brecher put additional emphasis on that point, saying, “this is a crisis that doesn’t discriminate, so if we’re all in it together, where’s the stigma?” She suggested that, if everyone came together to recognize that we are all affected in some way, it could crush the stigma surrounding the opioid crisis.

In the meantime, with each new training session, more people acquire and learn how to use Narcan, becoming empowered to prevent opioid overdose deaths.

“It saves lives,” Brecher said. “It’s as easy as that.”

Comments are closed.