A Transformation in Care – JGS Lifecare Unveils a New Rehabilitation Center

The hallways in the Sosin Center for Rehabilitation are wide, allowing for freedom of movement for multiple individuals going about the business of regaining their independence.

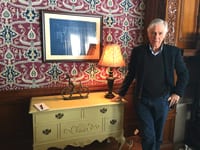

The bedrooms, as HCN observed on a recent tour, are simple but elegant, with mounted flat-screen TVs and adorned with paintings created by local artists. The bathrooms are large, well-appointed, and completely accessible to people with ambulatory challenges, and the spacious common living room is bathed in natural light.

“When we show people the Sosin Center, it speaks for itself,” said Susan Halpern, vice president of Philanthropy for JGS Lifecare, which opened the Sosin Center to short-term residents this month. “It’s the kind of environment where you’d want your loved ones to be cared for.”

The facility is named after George Sosin, a JGS volunteer, family member, former resident, and supporter who left $3 million dollars to JGS Lifecare in support of the center, the largest contribution received in JGS’s 104-year history. It contains two households, each designed to accommodate 12 short-stay residents. All 24 rooms are private, with full baths, and each home has a shared living room, dining room, den, kitchen, and porch, which provides seasonal access to the outdoors.

JGS unveiled the Sosin Center and the neighboring Michael’s Café — which connects the short-term rehab facility with the Leavitt Family Jewish Home, the organization’s nursing home — as part of phase 1 of Project Transformation, a multi-pronged endeavor to, well, transform JGS’ many senior-care elements into facilities that truly reflect 21-st century healthcare.

Notably, JGS Lifecare partnered with the Green House Project to implement a small-house model of care at the Sosin Center that is slowly becoming recognized throughout the industry for its success in reducing medication use and rehospitalizations, while affording greater socialization and interaction with caregivers.

Martin Baicker, president and CEO of JGS Lifecare, noted that more than 64{06cf2b9696b159f874511d23dbc893eb1ac83014175ed30550cfff22781411e5} of all short-stay residents at JGS are successfully discharged to the community, which is more than 10{06cf2b9696b159f874511d23dbc893eb1ac83014175ed30550cfff22781411e5} above the national average, but he expects the percentage to rise further at the Sosin Center.

The Green House model extends well beyond aesthetics, Baicker said, encompassing a three-pronged philosophy — real home, meaningful life, and empowered staff.

The first element is an effort to make short-term residents feel at home, not on some institutionalized schedule. “You wake when you want, go to sleep when you want — and it also looks like your home, architecturally,” he said.

Meaningful life means giving people choices in their day, and the small number of units allows residents to build strong relationships with the staff, he went on. “They feel a real sense of engagement.”

As for empowered staff, this might be the most important element of all, Baicker noted. Typically, he noted, an organizational chart extends from the top down, but here, it’s a series of concentric circles with the resident at the center, and the certified nursing assistants representing the second circle. “They provide personal care, cooking, laundry, light housekeeping, activities — and this is given by the same person spending an awful lot of time with the resident, getting to know them.”

The CNAs are supported by nurses; physical, speech, and occupational therapists; and perhaps a doctor, but still essentially make the day-to-day decisions about how the house is run, he explained. “That is totally, radically different than running a traditional nursing home.”

Person-centered Care

Of course, the Sosin Center isn’t a nursing home, which is why Halpern is happy that short-term rehab residents at JGS are no longer sharing space at Leavitt. “It’s not beneficial for someone to come in for rehabilitation and cohabitate with people in long-term care. They’re here short-term, getting ready to go home.”

Baicker agreed. “People in short-term rehab don’t want to feel like they’re in a nursing home.”

The Green House philosophy represents a stark change in the way the healthcare industry traditionally frames short-term rehab, Halpern added. “It’s person-centered care. You empower the residents to make decisions about how to model their daily lives and routines — when they get up, what food they eat. They have more say in their actual caregiving.”

Baicker said the outcomes of the Green House model have been impressive at other facilities that utilize it. Patients tend to need less medication, eat more food — because the scents of meals being prepared where they live activates their appetite — and engage in life in a more dynamic way, since they’re constantly engaged with the staff. “All those things combine to improve outcomes.”

Much of the rehabilitation incorporates activities residents will conduct once they’re back at home, from reaching shelves and preparing food to washing and bathing, said Susan Kline, who is co-chairing the $11 million capital campaign for Project Transformation with Stephen Krevalin. Both are longtime volunteers with the JGS Lifecare organization and former chairs of its board of directors.

Most Sosin residents will come from hospitals, but some from other settings, and while a small number may wind up in nursing homes, that’s rare; the idea is to prepare individuals to return to their homes and independence.

“The outcomes have proven to be much more successful in this setting than what occurs in other areas,” Kline added.

When Baicker came on board in 2012, JGS was already busy strategizing for the series of changes that would eventually become Project Transformation, including planned improvements to short-term rehabilitation and assisted living, as well as a revamp of the adult day health program to better serve a growing population of seniors in the early stages of dementia.

But he was one of the first in the organization to promote the Green House model, and when the board responded positively, team members started paying visits to other facilities that had incorporated it, from Mary’s Meadow in Holyoke to the Leonard Florence Center for Living in Chelsea.

“The board did their due diligence and decided this is the way we’re going to move,” he said. “And, ultimately, we want to expand this model to the long-term portion of the nursing home.” Indeed phase 2 of Project Transformation will turn to modernizing two 40-bed wings of the Leavitt Family Jewish Home in the Green House model.

Construction of the 24,000-square-foot Sosin Center and the adjoining kosher café began in June 2015, and both were dedicated at a ceremony last month shortly before their official opening.

The café is dedicated to the memory of the late Michael Frankel, who was an outspoken advocate for Project Transformation, Halpern said. “Naming the café in his honor is a permanent tribute not only to Frankel’s extraordinary commitment to the care of our elders at the highest standards, but also his vision for JGS Lifecare for generations to come.”

Krevalin hopes the café serves as a “beacon for the community,” noting that it connects the nursing home and the Sosin Center and is not only an ideal meal spot for residents, families, and staff, but for the public as well. “We’re hoping the community supports it.”

Ahead of the Curve

Project Transformation is far from the first time JGS leadership has moved away from traditional, stale facility design, Halpern said. As far back as the 1990s, the organization was renovating the nursing home and designing the Ruth’s House assisted-living facility to be more homelike and less institutional. “It’s all about making people feel comfortable in the environment where they’re living. The nursing home was built at a time when nursing homes were like hospitals, with nurses’ stations.”

Twenty years ago, a shift to a more home-like setting was still an innovative idea in healthcare, Baicker said. “You can’t underestimate the forward thinking of the leaders of this organization, making the common areas and dining areas less institutional. This [Project Transformation] is the continued evolution of that.”

“And believe me,” Kline added, “we’re already thinking about what’s next.”

Ruth’s House underwent some improvements as part of phase 1 as well, and phase 2, in addition to modernizing the nursing home according to the Green House model, will relocate and expand Wernick Adult Day Health Care to include a specialized Alzheimer’s program.

All this takes money — both phases were initially budgeted at $20 million but could eventually approach $23 million, Krevalin said — and more than 150 supporters have already contributed some $8.5 million to the capital campaign, which had an initial goal of $9 million but will be extended to $11 million.

“The initial response is heartening. It shows that many donors already understand the impact that our new facilities will have on the quality of life of our elders and others we serve,” Krevalin said. “Once people see Project Transformation, they will understand its impact, and they will want to be part of it.”

Comments are closed.