Aiming High New Law Targets the Soaring Cost of Healthcare

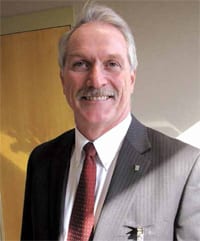

Daniel Moen wasn’t surprised by the healthcare cost-containment bill passed by the state Legislature and signed into law by Gov. Deval Patrick over the summer. Because he’s already been working toward similar goals.

“If anything, it gives us more urgency on looking for ways to improve patient care and reduce the cost of healthcare overall,” said Moen, president and CEO of the Sisters of Providence Health System, which includes Mercy Medical Center. “The target the state set for a cap on healthcare costs is certainly an ambitious one, so if we’re going to make that happen, change is going to have to occur faster than it has in the past — for all hospitals.”

But he’s not ready to say the goals — which mandate that healthcare costs in the Commonwealth cannot rise faster than the gross state product from 2013 through 2017, before dipping to GSP minus 0.5{06cf2b9696b159f874511d23dbc893eb1ac83014175ed30550cfff22781411e5} after that — are unrealistic.

“I think they’re very challenging, but I think if everyone pulls together, they’re achievable,” he told HCN. “And even if we don’t get all the way to the target, we’ll be moving in the right direction. Even if we miss that by some amount, we’re still initiating cost savings for the Commonwealth and the residents of the state. I’m a big believer in challenging goals, because they get everyone’s attention, and I know we’re going to do everything we can to make that come true.”

Upon signing the bill into law, Patrick said that “we are ushering in the end of the fee-for-service care system in Massachusetts.”

Indeed, the dramatic goals of the law — many hospitals and other providers will have to slash their costs by nearly half — will essentially quicken a move toward accountable-care organizations (ACOs) already underway across the state.

Under this care-delivery model, also known as a ’patient-centered medical home,’ a diverse group of providers — doctors, nurses, specialists, therapists, nutritionists, etc. — are assigned to a patient and are responsible for his or her care year-round. In turn, they are paid a set fee for providing that care. The payment structure discourages superfluous procedures — a hallmark of the fee-for-service model — but built-in quality metrics simultaneously guard against undertreatment because, if a patient’s condition worsens due to inadequate care, no one gets paid.

Still, even Moen, whose health system has been out front of most others in developing an ACO model, says the law isn’t some trivial tweak. “The legislation calls for 80{06cf2b9696b159f874511d23dbc893eb1ac83014175ed30550cfff22781411e5} of Medicaid recipients to be in some sort of alternative contract by 2015. That’s a very rapid transition. We’re going to have to take some of these ACO concepts we’ve learned and apply them to much bigger groups of patients than we have in the past.”

That said, most players with a stake in the Bay State’s healthcare economy understand that something needed to be done, especially after the Commonwealth’s 2006 health-reform law increased access to care without addressing the cost issue.

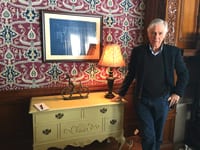

“Everyone agrees that the current path we’ve been on is unsustainable,” Peter Straley, president of Health New England — the health plan based in Springfield with more than 120,000 members statewide — told HCN earlier this year. “Financially, the rate of growth in healthcare costs has far exceeded the country’s ability to afford it in the near term, and there needs to be a fundamental change in the way healthcare is delivered and financed.”

The new law certainly does that — and it’s got the industry’s attention.

The Enforcers

That’s partly because of the way the law will be funded and enforced.

First, a $165 million surcharge is being levied against health insurers, and a $60 million surcharge against larger hospitals, in order to create a trust fund. These funds will go toward efforts such as a prevention and wellness program and community-hospital infrastructure upgrades, as well as programs to reduce the rates of preventable chronic diseases such as obesity, diabetes, and asthma.

The law also calls for the formation of a commission to simultaneously track healthcare costs and performance. All providers must comply with the performance targets or face fines of as much as $500,000.

The bill was spurred in part by reports issued over the past two years by the state Attorney General’s Office, one of which asserted that “the commercial healthcare system does not pay for care based on value. That is, wide disparities in prices are not explained by differences in quality, complexity of services, or other characteristics that might justify variations in prices paid to providers. Instead, prices reflect the relative market leverage of health insurers and health providers.”

After the law’s passage, Attorney General Martha Coakley praised the measure for addressing that market leverage and giving her office the power to “address negative impacts on the marketplace.”

Mercy’s early advocacy of cost efficiency and the ACO concept have prepared it for this moment, Moen told HCN. “We’ve shown here that we can provide very high-quality care, but do so at reduced costs. My hope is that, in the long run, patients are going to have more support and guidance going forward.”

He said the medical-home model gives patients more attention and guidance while aiming to keep them well and away from costly procedures and hospital stays. “Not only can we bend the cost curve, but I think we can get even better patient outcomes, especially for patients with chronic illnesses, like congestive heart failure, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, diabetes, and pneumonia, especially for compromised elderly patients.”

The law allows much more care traditionally given by doctors to be delegated to physician assistants (PAs). Meanwhile, “I think we’ll see a lot more care rendered in the home, more monitoring in homes,” Moen said. “We’re seeing some exciting new products coming out for monitoring patients and their health parameters at home.”

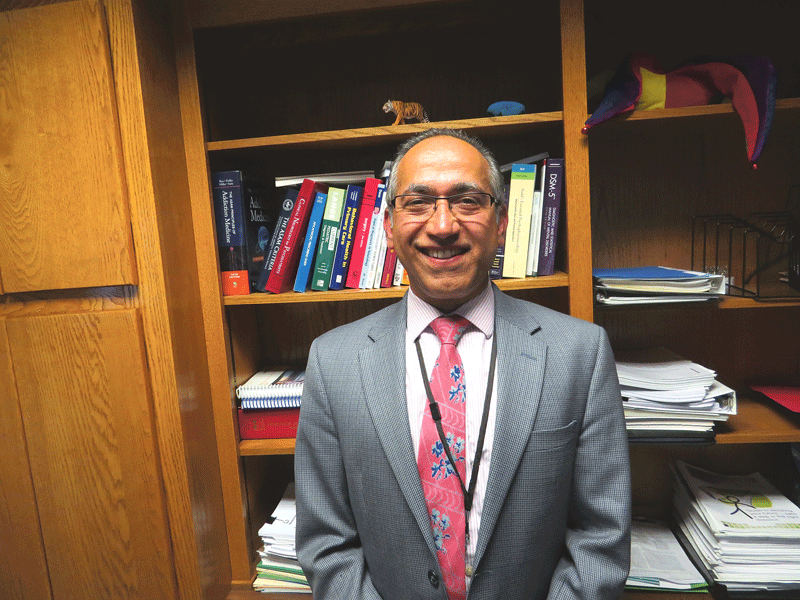

Dr. Richard Aghababian, president of the Mass. Medical Society, questions the classification of PAs as primary-care providers. In addition, “we are concerned about the impact of the bill’s very stringent reporting requirements on the smaller medical practices in the Commonwealth,” he said. “We will look to clarify how small practices will be impacted by the costs and burdens associated with reporting to new entities established by the legislation.”

Still, Aghababian is pleased that lawmakers took the action they did.

“The Legislature has produced an ambitious health care road map for our Commonwealth,” he said. “It seeks to make healthcare affordable for the residents, businesses, and government of Massachusetts, while fostering quality, access, and innovation. In many cases, the legislation strikes a responsible balance between the role of government as oversight entity [and] the rights of private-sector entities to operate responsibly.”

He also praised the inclusion in the law of the ’disclosure, apology, and offer’ model of medical-liability reform that the MMS has long championed, one that requires a six-month ’cooling-off’ period between an adverse incident and a lawsuit, and also bars a doctor’s apology from being admissible in court — steps that proponents say will foster a climate of safety and openness.

New Frontier

One problem the law does not address, Moen noted, is an ongoing dearth of primary-care physicians, especially new PCPs entering the field.

“They’re such a key player in this whole process,” he said. “They manage the patient’s journey through the healthcare system, and that’s something that we’re going to need to address going forward. If we’re going to be successful with this transition, we’re going to need more physicians’ assistants, more advanced-practice nurses, as well as primary-care physicians.”

But Moen embraces much of the thought behind medical homes and preventative care. “Keeping people well has an immediate, up-front cost, but the long-term savings to the system is going to be significant.”

Meanwhile, the state’s healthcare industry must grapple with what promises to be a dramatic shift in how services are provided and paid for — or at least the first part of that shift.

“Clearly, the transformation of healthcare is only beginning,” Aghababian noted. “There is still much more work to be done.”