Every Step of the Way Navigators Guide Cancer Patients Along Their Journey

The five-year survival rate for breast cancer, nationally, is 89{06cf2b9696b159f874511d23dbc893eb1ac83014175ed30550cfff22781411e5}.

At Holyoke Medical Center, it’s 95{06cf2b9696b159f874511d23dbc893eb1ac83014175ed30550cfff22781411e5}. And Jolene Lambert believes she knows part of the reason why.

Lambert is HMC’s ‘cancer care navigator,’ working with breast-cancer patients from their initial diagnosis through the often-difficult journey of treatment and recovery. She has also spearheaded community-outreach efforts to persuade women to be screened for breast cancer in an effort to find early-stage disease before it spreads.

Since she took the position less than a year ago, Lambert has found striking success on both fronts. All the patients she helps as navigator are 100{06cf2b9696b159f874511d23dbc893eb1ac83014175ed30550cfff22781411e5} compliant with getting to their medical appointments, taking the proper medication, and following other treatment recommendations — all of which enhances their long-term odds of beating the disease.

At the same time, the hospital has become more visible with community efforts to convince healthy women to get mammograms. “Some people are afraid to get it checked,” she said, “but the sooner you get it checked, the greater your chance of survival.”

The overarching idea, she explained, is that cancer is a frightening and often confusing subject, and helping women, well, navigate it will ultimately save lives.

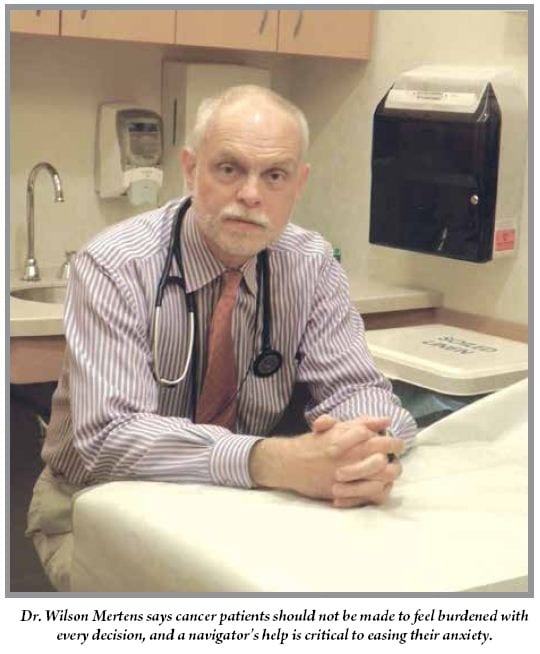

“Patients absolutely require assistance navigating the very complicated silos of our healthcare system,” said Dr. Wilson Mertens, medical director of Cancer Services for Baystate Health. “I would consider navigation to be part concierge service and part rapid contact for patients, to help them manage their symptoms and side effects.”

Baystate offers navigation across a number of cancers, while Holyoke will expand its program beyond breast cancer early next year.

Yet, “I think this concept really started in breast centers across the country because of the complications associated with moving patients from a screening scenario to a biopsy and ultimately surgery, if that’s required,” Mertens said. “Moving through all those steps is complicated, and patients are bewildered when they have to arrange it themselves. They often don’t know how to take the next step, and care is increasingly fragmented.”

The idea behind a navigator, Lambert said, is to give a cancer patient a resource who will guide them every step of the way — in the case of breast cancer, from an abnormal mammogram through all treatments and follow-up. One of her roles is to ensure that the process moves quickly, because patients want answers.

“Patients who are seen in the women’s center meet with the navigator,” she explained. “If they have an abnormal mammogram, they are called on the phone right away to come back for more films, and if they need a biopsy, they are seen within two days for that. The biopsy results are then reviewed with the physician who ordered the mammogram, and they follow up within two days to schedule their surgery.”

But the navigator’s services don’t end there. “If they need rides to appointments, we can help them, or if they don’t understand what the physician is saying to them, we go with them to the appointments so we can explain to them in simpler terms what their care should be,” she told HCN. “I start with the patient’s positive diagnosis and then follow the patient through her care — through surgery, through chemo, through survivorship — to make sure she’s making her appointments, following up, and not getting lost in our healthcare system.”

And it’s a trend becoming much more evident nationwide, she noted. “It is eventually going to be mandatory for all hospitals to have a navigator for cancer; we just happened to start a little early.”

Breaking Down Barriers

The concept of patient navigation was first developed by Dr. Harold Freeman in Harlem, N.Y., as an effort to reduce disparities in access to diagnosis and treatment of cancer, particularly among poor and uninsured people.

“During his practice, he realized he was seeing a lot of women who presented to him with stage 3 breast cancer,” Lambert said. “He felt there should be some way to get to these people because there is a cure for breast cancer if it’s detected early enough.

“So he devised a whole navigator program — not only following people through the disease, but getting out there in the community, getting people to their scheduled mammograms, offering them rides, and preventing barriers to getting mammograms, whether they don’t have insurance, they’re afraid, they don’t have transportation, or they don’t want to pay the co-pay, but would rather spend the money to feed their families. He helped them overcome the barriers to get the care they need.”

In 2007, with a $2.5 million grant from the Amgen Foundation, the Ralph Lauren Center for Cancer Care and Prevention established the Harold P. Freeman Patient Navigation Institute to train organizations in patient navigation. The core principles of the institute — which Lambert has attended — include:

• Informing people about the need for recommended examinations and providing timely access to such examinations;

• Eliminating any barriers to timely care across the entire healthcare continuum, and

• Eliminating any barriers to timely diagnoses and treatment in patients who have abnormal or suspicious findings.

Lambert said Holyoke’s program takes seriously the concept of breaking down barriers to care. “If people don’t have insurance, we write to drug companies and get them free medications — anything we can do, we do. We’ve gone as far as buying shoes for patients.”

Traditionally, one of the major barriers to patient compliance has been frustrating lags between diagnosis and consultation. When Lambert became navigator, she reviewed every patient’s chart and noticed a lag time between finding an abnormal mammogram and the resulting biopsy or surgery — in some cases, almost four weeks.

Now, “breast cancer patients are usually seen in one or two days. Some patients who are anxious about their diagnosis have been seen the same day,” she said. “It’s a relief for the patient. I’ve had patients say to me, ‘this would have been my first appointment at a different institution, but here, I already have three treatments under my belt.’ We’re really trying to get people treated quickly.

“Imagine having breast cancer and waiting three weeks for an appointment, or even two weeks,” she added. “I want to be seen the next day.”

At Baystate, Mertens said, navigators tend to work with certain doctors, or the same type of cancer, and they are considered a critical part of the cancer-care team.

“Cancer care has become more complicated,” he told HCN. “Every disease, every patient requires a different set of services and support. What a head and neck cancer patient might need in terms of surgery, chemotherapy, and radiation are very different from a breast-cancer patient, and a colon-cancer patient needs a whole different set of players and a different structure.”

Navigators who are well-trained in certain diagnoses are able to effectively answer patients’ questions and guide them to the right resources. “If we don’t provide that kind of support, the patients would be left to sort it out for themselves,” he continued. “But we don’t require patients to be their own physicians; we really need to be able to provide that to them.”

Meanwhile, navigation benefits physicians by making sure patients do what they’re instructed to do. Mertens used the example of someone whose primary-care doctor advises him to call a gastroenterologist to schedule a colonoscopy, but the patient decides to put it off. That’s just human nature, after all.

“Well, I can’t afford to have that with my patients,” he said. “If we need something arranged, we need to have it done. But I also think this is complicated enough that we need to own those arrangements.”

Community Minded

Lambert said no navigator program is complete without a public-outreach component that aims to identify cancers before they’ve advanced. She has distributed booklets throughout Holyoke, given several talks in the community, and recruited four physicians and two nurse practitioners for a free breast-cancer screening in March.

“We’re trying to reach all those people,” she said of such efforts. “In October, we’ll be at Stop & Shop booking mammograms on laptops.”

Once they’re in the system — particularly if a doctor detects early-stage breast cancer — she said patients are grateful that someone gave them the nudge to get checked. But she also deals with cultural barriers to care. “A lot of patients have certain religious beliefs, and think they have cancer because they’ve done something bad in their lives.”

Whatever the barrier, Lambert said, her job is to help break through it to get locals the help they need. After all, the mortality rate from all cancers combined has fallen to one-third what it was 40 years ago, and “immediate care and follow-up care are a big plus for these people.”

Patients are grateful for these targeted efforts to treat their cancer and keep them healthy, Mertens said. “They really appreciate the relationship. They spend a fair amount of time contacting the nurses, and the amount of information they receive is very robust.

“I think that it’s a great comfort for them,” he added, “and it’s a comfort for us on the physician side to know they have another healthcare professional with a deep, profound knowledge of what the patient is going through and can get the appropriate services they need.”

One challenge for the future, Mertens noted, is the still-unclear effect of healthcare reform, and new models of treatment like accountable-care organizations, on patient navigation. “There’s no specific payment for navigation, even though we think it’s critical and needs to be provided,” he said. “We’re not sure exactly what it’s going to look like.”

Still, the trend in oncology has been toward more navigation services, not fewer. And that’s bringing a measure of comfort to patients during some of the most difficult times in their lives.

“I had someone say to me the other day, ‘I don’t want to go to Holyoke; I had a bad experience there,’” Lambert said. “I said, ‘try it again; I’ll go with you.’ She said, ‘you would?’”

And she did just that, relieving the anxiety for one more woman in need. “If you don’t have a medical background nowadays,” she said, “you are lost — very lost.”

And when you’re lost, a navigator sure comes in handy.