Future Stars – John Robison’s Auto-repair School Helps ‘Different’ Students Succeed

Growing up in the 1960s, a victim of abuse at home and an inability to fit in socially at school, John Robison had every reason to worry that he wouldn’t find success in life.

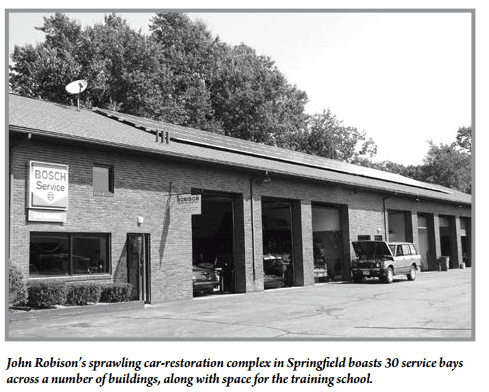

Yet, he did. Diagnosed as an adult with Asperger’s syndrome, which finally began to explain why he was different, Robison is the author of three bestselling books, a former electrical engineer who pioneered several innovations in the world of rock music, and currently the owner of J.E. Robison Service, a sprawling auto-repair and restoration complex on Page Boulevard in Springfield.

And now, by partnering with a special-education high school on the TCS Automotive Program — a vocational training center based at his workplace — he’s helping teenagers with the same challenges he faced gain the skills and confidence they need to succeed in the auto-repair field.

It’s a unique endeavor, but Robison has never been one to do things in the traditional way.

“I was always into cars and electronics,” he said of a set of interests that bordered on obsession in his younger years — a common trait among people with Asperger’s. “When I dropped out of high school, I taught myself about electrical engineering and found success as the American engineer for Pink Floyd. Then, a lot of big bands in the ’70s used our sound equipment. I’m best known for the work we did for KISS, engineering all their special-effects instruments” — such as custom guitars equipped with fiery smoke bombs.

After that, he got a job as an engineering manager in the corporate world, but disliked the experience. “I really didn’t understand the dynamics of the company. I decided, rather than be somewhere I didn’t really know what was going on and didn’t feel I fit in, I’d start a business of my own,” he said.

“The other skill I felt I had was fixing cars,” Robison continued. “But I wanted to fix cars that people cared about, thinking that somebody who’s a real car enthusiast would be interested in dealing with someone like me who had a real love of machinery, and that proved to be correct.”

His business — which specializes in repairs of luxury European models such as Rolls-Royces, Porsches, and Land Rovers — began as a part-time activity in South Hadley 30 years ago, and has since evolved into an extensive restoration and repair complex boasting 30 service bays, making it the largest independent garage complex west of Boston. And, unlike the service facilities of large area auto dealers, he said, he’s eschewed the sales side, which would only distract him from his mission of “fixing things.”

Some things don’t need fixing, of course, and today, thankfully, people tend to be much more aware of children on the autism spectrum, unlike Robison’s parents, who toted him to several mental-health professionals who labeled him lazy, angry, or even socially deviant, and said he might have to be institutionalized if his inappropriate behavior continued.

Just because the medical community and parents understand autism and Asperger’s much better today, however, doesn’t mean their challenges aren’t daunting. But Robison knows they can make their way in the world — after all, he’s exhibit A — and his new training school is demonstrating how.

Doing Things Differently

Robison has gained a much higher profile through his three books: Look Me in the Eye, which chronicles his life growing up; Be Different, which is filled with practical advice for “Aspergians, Misfits, Families and Teachers”; and Raising Cubby, a memoir of his unconventional relationship with his son, who also was born with Asperger’s.

And with that higher profile has come a greater sense of responsibility.

“Ever since my first book, Look Me in the Eye, was published, people have come here to see what we do, and they’ve asked for years about apprenticing autistic family members in the automotive trade,” he explained. “I’ve always tried to do things to help the community. Before I knew about my own autism, I worked with abused kids at places like Brightside and the jail because I grew up in an abusive environment; I would have been a kid taken by Social Services had I grown up today and not in the ’60s. So I’ve always felt an affinity for young people with challenges.”

Learning that autism was the root of his social challenges was a breakthrough, and he’s since considered how he could blend his career with a mission to help kids in similar circumstances. The answer came through a partnership with the Northeast Center for Youth and Families, which maintains a high school in Easthampton for teenagers with developmental challenges.

Specifically, the school, which serves students from all over Western Mass., opened the first high-school program licensed by the Massachusetts Department of Special Education that teaches young people the auto-repair trade in a location where the work actually happens. Students alternate spending a week at the high school, then a week at J.E. Robison, throughout the year.

“As revolutionary as that seems, that’s really how humanity learned all throughout history; they learned trades at the side of a master,” Robison said. “Whether that meant assisting a priest in his duties, clerking for a lawyer, or helping a blacksmith, they learned the trade at the side of a person who did it. We’ve lost sight of that and now teach in a vacuum, in this artificial high-school culture of bullying and things don’t happen in real life. One of our goals is to fundamentally change that.”

Of course, the students still must complete their regular course of high-school study, Robison said as he walked HCN through a small building set aside for the TCS Automotive Program, where students use cutting-edge equipment — much of it donated by Bosch Auto Parts — to work on cars, also mostly donated. In a small classroom, an instructor uses a white board to teach the business side of the auto-repair industry. A full-time special-ed assistant, a school psychologist, and school nurse also staff the program.

“This is the vocational part of the campus. These students will be in academic classes back at the main campus next week, and another shift will be here next week,” Robison explained. “Our students have to meet all the regular Massachusetts requirements for graduation from high school; this is not a program where they learn skills instead of high school — they’re learning a trade in addition to meeting high-school requirements. So it’s a harder program. Interestingly, students in this program are progressing faster than similar students in conventional vocational programs.”

It’s also a more intensive education than a traditional high school, with student-teacher ratios as low as 3-to-1 or even 2-to-1 at times. Robison often takes the students on “rounds” through the facility, much like medical students make the rounds in hospitals. But more often, they’re learning by doing.

It’s not a program for any teenager interested in cars, however. “We are a licensed special-education high school, so you have to have an IEP [individual education plan] in Massachusetts, which qualifies you for special-education services. Parents talk to the school district, talk to our admissions staff, and make sure the students are a fit for our program. We take the people we feel will be successful,” he explained, adding that the program is funded 80{06cf2b9696b159f874511d23dbc893eb1ac83014175ed30550cfff22781411e5} by the state and 20{06cf2b9696b159f874511d23dbc893eb1ac83014175ed30550cfff22781411e5} by each student’s local school district.

“We’re closely overseen by the state,” he added. “In fact, we’re probably more closely supervised than the public schools, which are mostly funded by local tax revenue.”

Available to All

Robison stressed that he wanted to create a program that operates in the public special-ed realm, not a private school.

“It was very important for me to work with public-school students. I didn’t want to create an elite program for wealthy kids; I wanted a program where any kid who needs services, who qualifies, could attend,” he said. “It’s entirely funded by the state Department of Special Education and local school districts. That’s really important. I want to deliver an educational model the public can benefit from, not just those who can afford private-school tuition.”

The school isn’t only for teens on the autism spectrum, however. Massachusetts offers special-education services to children on the basis of problems they have in school, as opposed to a medical diagnosis, he explained. “If you can’t organize yourself to do assignments in class, it might be due to a cognitive challenge, it might be autism, it might be ADHD, they might come from an environment that’s traumatic. Any of these underlying causes might add up to not being able to do tasks in school. We take kids who cannot succeed in a regular school and who are not violent.”

It’s actually discriminatory, he said, to position a school as one that specifically teaches students with autism how to act. “What we can say is, ‘you had a problem in school with completing your assignments; you’ve been sent to the office 10 times for what the teacher described as defiant behavior. You’ve got a problem. We help young people organize their thoughts and help them succeed better. We think we can help you.’ We’re not telling you that you’re marginal, defective, or broken. Whatever the issue, you have these challenges in school, and we have a program we believe can help you.”

Despite the way society has become aware of autism over the past decades, Robison told HCN, stereotypes remain. “But we have a complex where we show our students, and show everyone who supports them, that people who are different can be the stars.

“We are one of the largest service complexes in Massachusetts, and we embrace diversity, and I think many people come to us for that reason,” he continued. “Sure, some people come to us to get their car serviced and know nothing except that we provide service and they want to get their oil changed or their brakes done. But we also have people come in here who want to be associated with people who have a social mission in addition to a commercial mission.”

He’d like to see these students’ interest in cars become not just a mission, but a career opportunity.

“People often have a vision of children who are different and wonder if they can ever grow up and support themselves,” he said. “Our commercial operations here are not subsidized by taxpayers in any way. We are very successful competing in the free market. We have cars here from Montana, Ontario, Virginia, Pennsylvania. Those cars are here because of our reputation, and it started with my fixation on cars and machines, which was characterized as a disability when I was a little boy. We’re kind of the embodiment of the idea that the traits that make a child seem disabled can make a technologist a star.”

If other teenagers in the program find similarly satisfying careers — whether as technicians or working on the retail side of auto repair — then the effort to open TCS will have been well worth it.

“We tell them, ‘this is the stuff you’re going to need to get hired,’” Robison said. “Nobody’s forced to be in this program; they’re here because they want to learn how to do this.

“We have to have teaching strategies to work with autistic people, work with victims of child abuse. But these are also people who just love cars,” he added. “So I see myself in many of these young people, and I’m very proud we’ve been able to make the school come true here.”

Comments are closed.