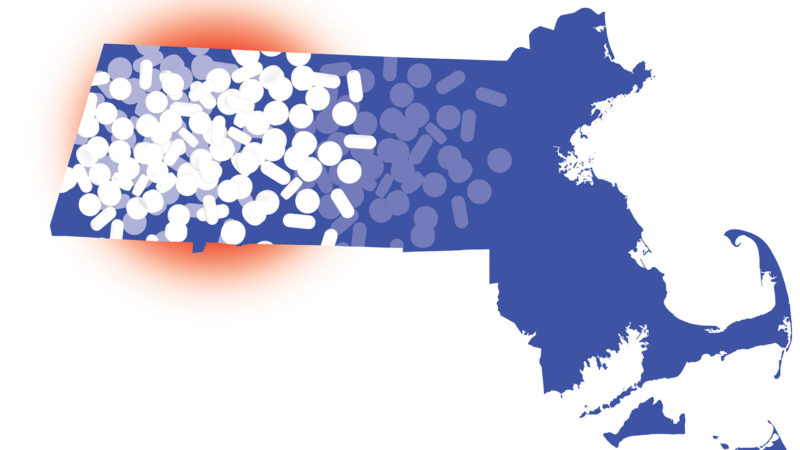

Overdose Deaths Decline Statewide, but Increase in Western Mass.

Persistent Problem

By JOSEPH BEDNAR

It’s a disconnect that has many health officials in Western Mass. worried.

On one hand, opioid-related overdose deaths in Massachusetts continue to decline, falling nearly 11% in the first six months of 2019 compared to the first six months of 2018, according to data released last month by the Massachusetts Department of Public Health (DPH). In the first six months of 2019, there were 938 confirmed and estimated opioid-related overdose deaths in Massachusetts — 112 fewer than the 1,050 deaths between January and June of 2018, the latest quarterly report shows.

On the other hand, that DPH data shows that, in 2018, while the rate of opioid-related overdose deaths decreased in the Commonwealth as a whole, the Western Mass. counties of Franklin, Berkshire, Hampshire, and Hampden experienced a 73% increase.

This finding is a major concern that may be attributable to a higher prevalence of opioid-use disorder (OUD) in some counties, higher opioid prescribing compared to the state average, and the extent of the deadly synthetic opioid fentanyl in the illicit opioid supply. Before 2018, the presence of fentanyl in overdose deaths was lower in Western Mass. compared to the rest of the state. Increases in fentanyl-related deaths in Western Mass. appear to be converging to state levels, where they are responsible for more than 90% of opioid-related overdose deaths.

“Even though some parts of the Commonwealth have seen a leveling off or reduction in the opioid crisis, it continues unabated in our region.”

“Even though some parts of the Commonwealth have seen a leveling off or reduction in the opioid crisis, it continues unabated in our region,” said Dr. Friedmann, chief Research officer at Baystate Health and associate dean of Research at UMass Medical School – Baystate.

At press time, Friedmann was getting ready to participate in a public forum discussing an issue brief prepared by the Massachusetts Healthy Policy Forum (MHPF) examining the impact of the opioid crisis in small and rural communities in Western Mass, which continue to suffer disproportionately from this disease despite progress statewide.

Across Massachusetts as a whole, the decline in opioid-related overdose deaths is occurring despite the persistent presence of fentanyl, which has risen to an all-time high. In the first quarter of 2019, fentanyl was present in 92% of opioid-related overdose deaths in Massachusetts where there was a toxicology screen. In 2018, fentanyl was present in 89% of opioid-related overdose deaths where there was a toxicology screen.

“Despite the battle we continue to fight against fentanyl’s presence in Massachusetts, the overall decrease in the first half of this year marks continued progress in decreasing opioid-related overdose deaths,” Gov. Charlie Baker said after the DPH released its latest statewide numbers. “We were pleased to work with our colleagues in the Legislature to invest more than $246 million this year in prevention, treatment, recovery, and education solutions to the opioid epidemic and remain committed to working with all levels of law enforcement on removing fentanyl from Massachusetts communities.”

Local Measures

On the local level, organizations have launched initiatives to slow opioid addiction, hopefully before it starts.

For example, Health New England (HNE) teamed up with leaders of Western New England University’s (WNEU) Pharmacy program to work together to reduce the number of prescription opioid in area communities. Through the Opioid Access Program, Health New England limits short-acting opioid prescriptions to a seven-day supply. HNE seeks to encourage doctors to rethink their prescription practices and keep unused opioids from piling up.

“The volume of tablets that gets into patients’ medicine cabinets was overwhelming,” said WNEU Associate Professor Natalia Shcherbakova. “It amounts to over 150 tablets, on average, of short-acting opioids — oxycodone, hydrocodone, etc. — for each Health New England member who has filled any short-acting prescription opioid in a given year.”

Many factors have contributed to the current opioid crisis, including social and socioeconomic issues. But ease of access to prescription opioids has been an important enabler. Many people with opioid addiction started with unused pills taken from a medicine cabinet.

“Since the epidemic was facilitated to a great extent by easy availability of prescription opioids through frequent and excessive prescribing practices, it can arguably be contained via the same route — reducing access,” Shcherbakova noted.

Health New England and WNEU’s Pharmacy team worked together to study the program’s results after a year and found that the number of HNE members filling short-acting opioid prescriptions for more than a seven days’ supply had decreased.

Because of the positive results, Health New England recently refined its access criteria. The program now requires permission for refills of cough syrups containing opioids after the initial fill — another small change it hopes is a step in the right direction toward reducing future cases of opioid addiction.

Meanwhile, earlier this year, researchers at UMass Medical School – Baystate announced they are participating in a federally funded study, called the National Rural Opioid Initiative, to better understand the opioid epidemic and available health services in rural communities throughout New England.

Friedmann, who is the principal investigator of the study, said the opioid-use disorder epidemic — with its increased risk of overdose and infection with HIV, hepatitis C, and sexually transmitted diseases — is the biggest public-health challenge facing rural New England in decades.

“We are learning from people who know firsthand what it’s like to use opioids and inject drugs and live in a rural area — something that has been looked at very little in the past,” said Elyse Bianchet, a research assistant on the project.

Baystate is one of only eight institutions in the U.S. receiving funding to participate in the National Rural Opioid Initiative. The research grant is from the National Institute on Drug Abuse, the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, the Substance Abuse Mental Health Services Administration, and the Appalachian Regional Commission.

The research team is based at Baystate Franklin Medical Center in Greenfield, but is working in locations throughout the Interstate 91 corridor all the way up to the Canadian border. They will map opioid use and infectious disease and compare that distribution to the availability of substance-use treatment, harm-reduction programs (such as needle exchanges and naloxone distribution), and medical care for infectious diseases. This data, they hope, can be used to help create better, more accessible services, and result in reducing overdose deaths and the spread of infectious diseases.

Recruitment is made challenging by the stigma surrounding addiction and the fear of law-enforcement common among those using opioids, according to Julie Kingsbury, clinical research coordinator. So researchers are using a referral-based system, known as respondent-driven sampling, designed to find members of hard-to-reach or hidden populations. In this study, participants get coupons to give to others who they know are using drugs. They also receive an incentive if someone they have referred joins the study.

“Someone injecting heroin every day is not having fun,” Bianchet said. “It’s a lonely, painful, difficult place.”

Measure of Hope

Friedmann notes that myriad overdose-prevention and related disease-prevention measures exist, from better access to clean syringes and methadone and naxolone treatment to long-term treatment and support. Such programs are often more easily found in urban areas, but health officials in Western Mass., particularly its rural communities, are trying to move the needle.

For now, the statewide decline in overdose deaths provides both hope and evidence that recent prevention initiatives are making a difference.

“The data is a promising indicator that our investment in a multi-pronged, multi-year strategy to increase access to treatment for this complex disease and underlying co-occurring illnesses is helping to save lives,” said Health and Human Services Secretary Marylou Sudders. “We must remain committed as a Commonwealth to employing every tool we have at our disposal to reduce the impact of opioid addiction and overdose deaths and to provide hope and recovery.”