Study in Strategic – Thinking New Westfield State Leader Is Focused on Student Success

Ramon Torrecilha recalls that, maybe 18 months or so ago, he was a candidate for a number of advertised college presidents’ positions in several states.

But upon visiting the Westfield State University campus and talking with members of several constituencies there, he decided to drop out of several of those other searches, including the one taking place at another school in the Bay State. When asked why, he started with a quick answer that required a lengthy explanation.

“It was that kind of institution,” he told HCN, using that phrase to describe what he encountered as a student at Portland (Oregon) State University in the early ’80s. Like other schools at the time, it was suffering budget difficulties and undergoing staff reductions. The faculty that remained were dedicated and singularly focused on student success, he recalled.

“The relationship I was able to develop with faculty allowed me to have a transformative experience at Portland State,” he recalled. “And when I looked around here, I felt that Westfield State was very similar in that regard. You get a strong sense of community here.

“We’re student-centered; our faculty members are committed teachers, stellar researchers, and faculty that cares about student engagement,” he went on, clearly proud to shift the tense of his remarks to the present, and thus use terms like ‘we’ and ‘our.’ “So there was an alignment between myself and the kind of institution I was looking for, and Westfield State University.”

Beyond these characteristics, though, Torrecilha, who knew very little about the school before his first visit and was diligent in his “discovery process,” noted that there was something else about the institution that became apparent — and appealing — to him.

“The sense I got was that the institution was really ready to move forward — it was ready for the next stage,” he said, using a phrase with many applications.

For starters, it meant moving on from the controversy, and statewide negative press, that accompanied the ouster of his predecessor, Evan Dobelle, amid reports of extravagant and reckless spending practices — although Torrecilha believes the school has, by and large, already done that.

“There was an interim president in place [Elizabeth Preston] for two full years, and she did a tremendous job of stabilizing the institution,” he explained. “Westfield State is a very resilient institution; it has what we call good institutional bones. It showed to the higher-education community that it was much, much stronger than a hiccup in leadership.”

But that next stage also refers to a host of other initiatives at this school of roughly 6,000 students, from expanding programs, especially in healthcare, to broadening graduate programs and generating more momentum in regional and statewide efforts to get more people into college and then successfully on to completion of a degree program.

A sociologist by trade, Torrecilha will bring to his new position a deep understanding of multiculturalism and the issues confronting different demographic groups, but also his own opinions on how college presidents should approach their work, one forged through roughly a quarter-century in academia.

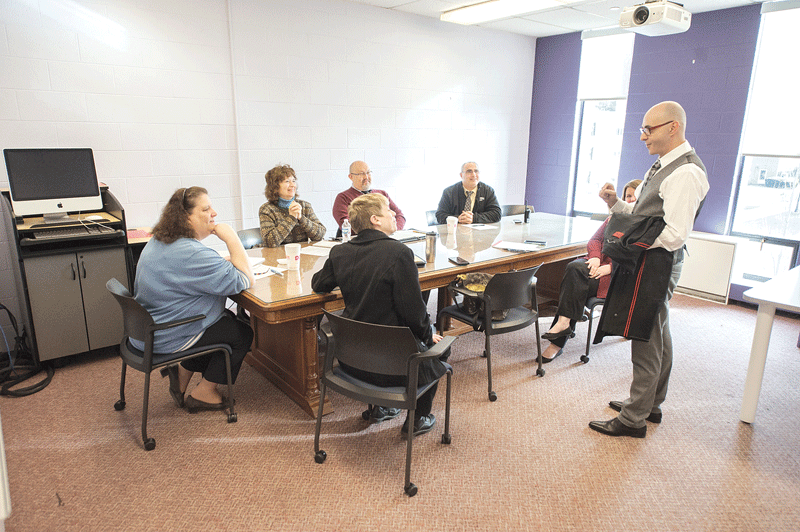

“When you think about it, presidents don’t run anything — presidents provide a sense of direction, identify priorities for the institution, and provide a vision and a map for how we’re going to get there,” he explained. “But it’s really the faculty and staff that run the place, so understanding how to do this and understanding the organizational psychology of the institution becomes really important in the presidency.”

For this issue, HCN talked at length with Torrecilha about his decision to take his career 3,000 miles to the north and east, and how he intends to lead efforts to draft that road map for taking this 178-year-old institution to the proverbial next stage.

Course of Action

Visitors to the president’s office at WSU — and a host of other spots on campus, for that matter — can pick up some intriguing reading material if they are so inclined.

Indeed, in an effort to fully communicate what he has seen, heard, and learned since arriving on campus in January — and also to set a tone for what he wants to happen next — Torrecilha has printed a compendium that details it all.

It’s called the “President’s First 100 Days Report,” with the working subtitle “Vision for a Model, Comprehensive Public Institution.” And it includes everything from a detailed accounting of the new president’s meetings since he took the helm — 102 with direct reports, 84 with campus constituents, 11 with the Westfield State Foundation, and five at alumni events, for example — to the results of an extensive survey of students, faculty, and staff.

Torrecilha said the purpose of the report was to put down in black and white (and a host of colors as well) the sentiments he expressed about where the school is and where he and those various constituents want it to go, and also state the basic tenets of a new strategic plan for the school.

That plan will have a number of key bullet points, including stated goals common to all of the Commonwealth’s public schools — increasing retention, improving graduation rates, and decreasing the so-called ‘achievement gap’ among state residents of different demographic groups. But there will be some more specific planks as well.

These include a broad push to strategically grow graduate programs, which will in turn provide financial and other sources of support for undergraduate programs; better engage alumni, many of whom go on to live and work in the Bay State upon graduation; and strengthening ties to the community, meaning both the host city and the region as a whole.

“Achieving student success does not come from just one mind,” Torrecilha writes in the report. “Currently, we possess the brushstrokes of a vision. But decisions about how we are going to achieve our goals is ongoing. The process is fluid and organic, and relies on collaboration from students, faculty, staff, and other partners.”

Roughly translating this passage, Torrecilha acknowledged that it’s one thing to put goals, aspirations, and visions down on paper. Making them reality is quite another.

“The next fiscal year will bring the hard work of taking ideas on paper and making them happen,” he explained, adding that the overarching goal, or assignment, is to make Westfield and the university there a true destination.

He believes the university’s ready — and he’s ready — to do just that.

And he’ll bring to the task a broad résumé of experience, one that includes everything from experience in the classroom to a host of administrative positions.

Our story starts at Portland State, where Torrecilha majored in sociology and became inspired by a faculty member to get the graduate degrees needed to teach that subject, which he did, with first a master’s at Portland State and then at the University of Wisconsin at Madison, which had one of the nation’s top programs in that field.

His specific fields of study were demography, poverty, and socioeconomic developments, and this would shape his teaching, starting at Berkeley College in New York, where he taught, among other things, a course titled “Minority Groups.”

In the course of doing so, he essentially refocused it — on sociological concepts, rather than specific demographic groups. He eventually wrote a paper with a graduate student on how to redesign such courses nationally, and it caught the attention of the American Sociological Assoc.

“The next thing I knew, they called me and said, ‘come to Washington and help us think about how to fuse multiculturalism into the curriculum,” he told HCN, adding that this began a stint as director of something called the Minority Fellowship Program and Minority Opportunities Through School Transformation.

From there, he went to the Social Science Research Council in New York, working specifically as director of the Public Policy Research Program on Contemporary Hispanic Issues, before shifting back to higher education and a stint first as director of Multicultural Programs at Mills College and then executive vice president of the Oakland, Calif. School.

He then served as provost and executive vice president at Berkeley College, before returning to Mills College and service in a variety of roles, including interim president. His most recent stop was as provost at California State University, Dominguez Hills.

By 1993, he said, he had made becoming a college president his stated goal, and he spent his career preparing himself for that eventuality.

“In academia, you have to sort of expose yourself to different things and have jobs in the many divisions that form a university,” he explained, “in order for you to harness the know-how and understanding of the different parts of the institution, and the sector.”

Which brings us back to last spring, and his decision to pull out of several presidential searches and focus on WSU.

Degrees of Momentum

Torrecilha said this choice came down to a word many use upon making a career decision of this kind: fit.

“In higher education, the question of fit, both from the standpoint of the candidate and the standpoint of the institution, becomes an important consideration,” he explained, adding that, in all matters that mattered to him, the fit was ideal.

He was looking for a school with a student-centered focus, and the school was looking for someone willing to make a substantial commitment to the school and the host city — and spent a year considering more than 400 candidates to find such an individual.

By commitment, Torrecilha said a stay that would be at least seven or eight years, out of necessity. “It takes that long for someone to really put some strategic initiatives down and then make them happen.”

As he talked about how he intends to go about meeting the goals set down in his first major communiqué to the WSU campus, Torrecilha said he will bring to the task an attitude, or mindset, far different than that of his controversial predecessor.

Summing it up, he said it comes down to putting the school, and especially its students, first — always. This sounds simple and quite obvious, he said, but some college and university presidents tend to forget this basic premise and make it about them.

“I want to serve as the president, but not be the presidency,” he said, choosing those words carefully. “It’s not about me, and as a sociologist I understand the differentiation.

“You bring to the job qualities that allow you to create that road map and enable you to work with members of the community,” he went on. “But you have to be able to put yourself on the side and think institutionally: ‘what’s the best thing for the institution?’ You have to remove personalities from that process.”

This is the approach Torrecilha says he will take to the various initiatives outlined in his “First 100 Days” report. These include efforts to expand and enhance graduate programs, thus making the school more of that destination he described, and for more types of students.

This strategic step will also help not only with broadening the school’s reputation — it has been known throughout its history as a teachers’ college, and more recently for criminal justice — but also in withstanding certain demographic shifts (something Torrecilha obviously understands) and especially smaller high-school graduating classes for the foreseeable future.

“Birth rates are declining, and the numbers of traditional college students are going down, and for this reason, most of our growth is going to come at the graduate level,” he said, citing, as one example, a new physician assistant master’s-degree program, the first of its kind for a public school in the state.

But those smaller high-school graduation classes means WSU, like all the other public schools in the Bay State, will have to become more diligent about helping students — traditional and non-traditional alike — enter college and then leave it with a degree.

This challenge explains many of the affiliation agreements between WSU and the area’s community colleges — programs that facilitate moving on to the four-year institution — and also why Torrecilha is a strong supporter of the state’s Commonwealth Commitment program, which incentivizes individuals (through rebates on tuition and fees) to enter a community college, graduate in two and a half years or less, move on to one of the state universities or UMass campuses, and wrap up a baccalaureate degree in no more than four and a half years.

When asked about the challenges WSU would face if a large number of students took the state up on its offer, Torrecilha replied simply, “that would be a really good problem to have.”

Applying Lessons

He was speaking about the state, the business community, and area cities and towns that would benefit from having a better-trained workforce. But he was also speaking about the state’s public schools and especially WSU, which embraces its role in training individuals for a global, technology-driven economy.

This is part of that ‘moving forward’ and ‘moving to the next stage’ vibe, for lack of a better word, that Torrecilha experienced when he first visited the campus on Western Avenue.

That vibe was a big factor in prompting him to take his name out of consideration for other presidents’ jobs and focus his sights on WSU. And it’s one he believes will take the school to the various destinations on the road map he’s helping to create.

Comments are closed.