The New Faces of Medical School – Baystate PURCH Program Puts Focus on Population Health

Like most first-year students, Kathryn Norman entered medical school in August not knowing exactly what to expect.

But there were certainly some things she never expected.

Like a curriculum that included a visit to the Hampden County jail in Ludlow, where she and fellow classmates talked with inmates about their health and well-being and learned first-hand how social issues and mental-health conditions have impacted their lives and put them on a path to incarceration.

Or a visit to a local food store, where teams were assigned the task of taking $125 in food stamps and buying a month’s worth of food for a single mother with diabetes and her daughter, all while trying to keep proper nutrition as the basis for the spending decisions.

Or a visit from an auto mechanic who would discuss the questions he asks a car owner to diagnose problems, with the goal of driving home the message that a similar methodology — and many of those same questions — would be utilized by a physician seeking to fully diagnose an issue with a patient.

But all this and more has been part of the first five months of experiences at what is known as the University of Massachusetts Medical School – Baystate, the Springfield campus, if you will, of the Worcester-based institution.

“The very first patient that I ever spoke to was someone who was incarcerated,” Norman said of her start in medical school. “And just getting to hear about the challenges these inmates had and bringing together the medical conditions they have, which are pretty complex, and the social conditions they have, that’s very exciting.”

That’s a word used often by the 22 students enrolled at UMass Medical, who spend one day every two weeks in Springfield and, more specifically, at the facility created by Baystate Health at the Pioneer Valley Life Sciences Institute on Main Street. They are there for a class devoted to developing their interviewing skills, something not often thought about when it comes to a medical-school curriculum, but a nonetheless critical part of the equation when it comes to being a good doctor, as Dr. Kevin Hinchey explained.

He’s chief Education officer and senior associate dean for Education at UMass Medical School — Baystate, and he said that, while students are mastering the art and science of asking questions, they are gaining a unique perspective on the many aspects of population health by hearing, and absorbing, the answers.

Such as those they heard while visiting an area homeless shelter.

“There was a gentleman there who has diabetes; the students were interviewing him, and he said he keeps a candy bar by the side of his bed,” Hinchey recalled. “When they asked him why, he said ‘because it’s nutrition, it has a lot of calories in it, and it doesn’t spoil.’

“This is one of the social determinants of health,” he went on. “We talk about a food desert in downtown Springfield … you can’t get fresh fruits and vegetables, so you get other foods. That conversation becomes important, because later, when you see that same person in your office and his blood sugar is 400, you might say that he needs insulin. But because you saw him there (at the homeless shelter), you say ‘no, he needs a refrigerator.’ It changes your concept of the disease and gives you a real example of people thinking, ‘as a doctor, I’m reacting to things; can’t I get more upstream and do some more prevention?’”

Indeed, through participation in an initiative known as PURCH (Population-based Urban and Rural Community Health), students are getting a different kind of learning experience as they work on their interviewing skills, one that Rebecca Blanchard, assistant dean for Education at UMass Medical School — Baystate, and senior director of Educational Affairs at Baystate Health, summed up by saying that what differentiates it is not what’s being taught, but how and where, and also in the way these experiences motivate students.

And to get that point across, she talked more about that visit to the homeless shelter.

“This is an interviewing class; students are building skills in interviewing — having a conversation to gain information. It’s also a track focused on how population health and disparities intersect in a human way,” she said, adding that, through their various experiences, students move beyond the act of treating sick patients and into the all-important realm of advocacy.

“They come back from these experiences asking questions that are advocacy questions,” she went on. “They ask ‘why?’ and ‘why not?’ and ‘how can we help?’”

For this issue and its focus on the healthcare workforce, HCN visited the Baystate facility and talked with Hinchey, Blanchard, and several students about the unique approach that is PURCH, as well as the many unique learning experiences they’ve already shared.

Body of Evidence

As he talked about the process of applying to medical schools and the factors that weighed on his decision concerning where to go, Colton Conrad, from North Carolina, started by saying he first focused on schools with respectable primary-care rankings and also an emphasis on patient care rather than research.

Those criteria put UMass Medical on his relatively short list, he went on, adding that, while he was applying, he noticed a secondary application “for this thing called PURCH.” Intrigued, he went on the website and did some reading.

Actually, it was only about three paragraphs, but it was more than enough to get his full attention.

“What I gained from those three paragraphs was that this was a branch of UMass Med School that was starting up the year I was starting school to take future physicians out of the classroom, out of a standard hospital setting, and get them involved in the community,” he recalled, “with the goal of better understanding the people and the patients they serve — to understand them on a deeper level than just illnesses.

“And I thought that was really cool,” he went on, adding that this quick synopsis was enough to prompt him to apply. And the visits to Worcester and then Springfield were enough to convince him that his search was pretty much over.

“It felt like … it wasn’t just a place where I wanted to be; the people also wanted me to be there,” he explained. “That was the first time I felt that at a medical school.”

With that, there was considerable nodding of the heads gathered around the conference-room table as HCN spoke with several students enrolled in PURCH.

Collectively, they used that word ‘cool’ several more times as they talked about both those experiences that take place, as that short description on the website noted, outside the classroom and outside the hospital, and also about what it means for their overall medical-school experience.

Norman said PURCH adds what she called “another layer” to her education, an important one not available in the traditional classroom setting.

“Our education has been so much more grounded in actually understanding real people and the real lives they have,” she said. “And these are opportunities that I haven’t seen our classmates in Worcester have.”

Betsy McGovern, from Andover, agreed, and to get her points across, she revisited her experiences at the Ludlow jail, which were memorable on many levels, but especially for the unexpectedly candid conversations between students and inmates.

“Our inmate was talking about his struggles with diabetes and his family history of diabetes, and he mentioned, very briefly, a domestic-violence incident that occurred between his family and his mother,” she recalled, adding that the students involved were at first unsure about whether to probe deeper on that topic, but eventually did, in part because the inmate was able and willing to open up, but also because it was important to do so.

Indeed, there are many contributing factors to one’s health and well-being, McGovern went on, and traumatic experiences such as witnessing domestic violence are certainly one of them. Asking patients about them is difficult and awkward, but it’s as important as asking them about their diabetes. And gaining experience with such hard questions — and the resulting answers — is a critical part of becoming a good interviewer and, more importantly, a competent clinician.

And something else as well — an advocate, said Prithwijit Roychowdhury, another first-year student known to his colleagues longing for something shorter and easier to pronounce as ‘Prith.’

He told HCN that, through their experiences in PURCH, students gain a greater appreciation for those social determinants and thus, perhaps, a better understanding of the importance of prevention, rather than simply treatment of illnesses.

“I think a lot of us are interested in being advocates and policymakers potentially, or even researchers working on policy or how well certain policies are working,” said Roychowdhury, who is from Worcester. “And to that end, getting a diverse exposure from a variety of different groups of people helps to contextualize the things you might want to advocate for.

“And as medical students who are interested in population health, we all know that it’s not purely the encounter with the patient in the examination room that matters,” he went on. “It’s about the broader context: what are the kinds of policies that are causing this particular patient to have a child who gets exposed to lead or arsenic, or are there reasons why a family has a long history of diabetes?”

All these comments help explain why the PURCH curriculum, and this interviewing class, were structured in this way, said Blanchard and Henchey, adding that the goal is to motivate students to look beyond the patient’s condition and to the big picture — the factors that made this condition possible and even inevitable, with an eye toward prevention.

“We’re getting students involved in advocacy and those discussions about what can be done to improve population health early on,” said Blanchard. “There’s genuine curiosity to be actively part of the solution, and it’s quite exciting for all of the faculty to see it from that lens.”

Learning Curves

Conrad told HCN that one of the most important aspects of the road trips taken by the PURCH students is the debriefing — his word — that goes on afterward.

“When we go out as a group for these experiences, we come back and we talk about them,” he explained. “And it’s really interesting to hear everyone’s perspective, because just about everyone in PURCH has different backgrounds, different life stories.”

And these debriefings have become learning experiences in their own right, he went on, using the trips to the homeless shelter and jail (half the class visited each one) as an example.

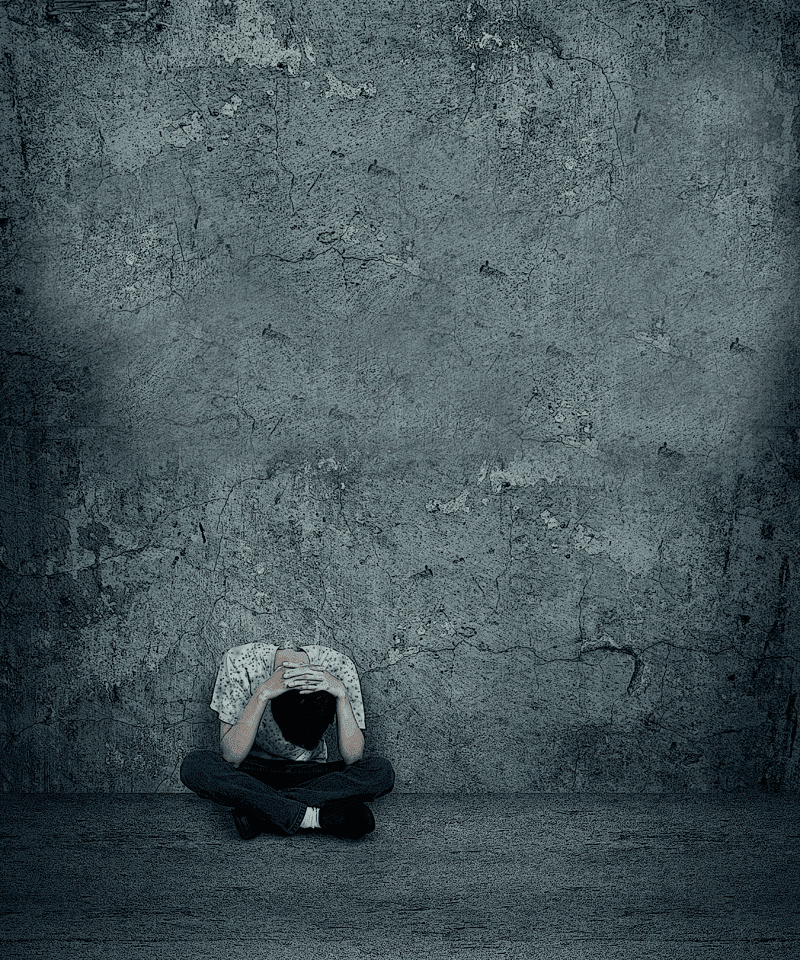

“We all came back from those trips, and it seemed like everyone had very similar stories even though we were with very different populations,” he explained. “We all found that most of our patients had these pre-existing, oftentimes mental-health conditions that were playing out in the worst ways in every aspect of their lives.

“It’s really easy to look at the prison population or the homeless population and make fairly gross generalizations,” he went on. “But after having our debriefing, it’s a little harder to do that, except to say that a lot of people have underlying issues that are affecting their lives so negatively that they are put in situations where they’re homeless or they’re incarcerated or they are drug addicts. Out of all these experiences, what I’ve gained the most is looking at people beyond what their particular illness is at that moment; whatever they’re presenting with that day isn’t even close to the full story.”

This, in a nutshell, is what PURCH is all about, and Conrad’s comments, and those of his fellow classmates, effectively bring to life that three-paragraph description of the program that drew them in and eventually drew them to Springfield.

There are many social determinants of health, and each one plays a role in what brings a patient to a physician’s office on a given day. Some of the biggest are the many challenges that are part and parcel to living at or below the poverty line, challenges that drive home the point that there are often huge barriers to doing the right thing when it comes to one’s health and well-being.

Which explains why that visit to the grocery store carrying $125 in food stamps was so eye-opening, said Norman, adding that there’s a big difference between reading about such issues in a book or news article and seeing them first-hand.

There were fruits and vegetables at this store, but they were too expensive and they would perish, she noted, adding that those pushing the cart had to steer it up different aisles.

Conrad, who was in the same group, was actually able to bring personal experience to bear.

“My family was on food stamps for a while when I was growing up, and I remember my mom having to make some of those tough decisions,” he recalled. “And it was weird to be in her situation but in a simulation.”

By the time the group arrived at the checkout line, the cart was full of rice, beans, pasta, and other items that were in bulk, inexpensive, and transportable, said Norman, adding that those who participated in the exercise left the store with large doses of frustration.

And that led Roychowdhury back to his thoughts about advocacy.

“We need to think about what we can do about these issues, such as the food choices that might lead to diabetes,” he explained. “Regardless of where we end up … if we end up in a hospital, what can we do to advocate for our board of trustees or our administration to help create and implement programs focused on education regarding diabetes or even creating a diabetes pump clinic?

“These are things already happening at Baystate and are concrete examples we can draw from,” he went on. “They give us a lot of insight into maybe how to implement these in our population health tool kit, not purely as a clinician, but as a population-health advocate.”

Outside the Box

Returning to that visit to the food store one more time, Conrad said it was quite lifelike, but not quite the real thing, and for several reasons.

Indeed, he recalls Roychawdhury, also part of his group, advising that they buy food with a lower glycemic index. “I said, ‘dude, I don’t even know what that means; how are we expecting the average person to make healthy choices for their diabetes based on a glycemic index when I don’t know what that is?’

“Also, we didn’t have a screaming kid in our cart as we doing our shopping, and we were able to take our cars; we didn’t have to take the bus and fit everything for a month into three bags,” he went on, adding that these missing ingredients would have made the assignment that much more difficult, as it was for some people who were tackling that exercise for real on the same day his team was.

The screaming child was missing, but just about everything else was there. It was real, hands-on, outside the box, and certainly outside the classroom.

As noted earlier, Norman and her classmates didn’t know quite what to expect in their first year of medical school. But they were definitely not expecting learning experiences like these.

Experiences that will make them better interviewers — and better doctors.

Comments are closed.