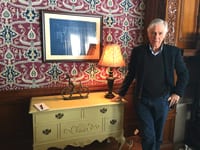

Course of Action Spiros Hatiras Set to Take the Reins at Holyoke Medical Center

Spiros Hatiras likened it to being homesick.

That’s how he chose to describe his mindset during what would become the latter stages of his tenure as chief executive officer of NIT Health in New York, a health-informatics company that specializes in the implementation of electronic medical records for hospitals and healthcare systems.

He enjoyed the work and found it rewarding in some respects, but the more he was in that position, the more he realized just how much he missed what he would later describe as his passion — leading a small community hospital.

“I really missed hospital administration,” said Hatiras, who joined NIT after a two-year stint as president and CEO of Hoboken University Medical Center (HUMC), where he also served as chief operating officer, vice president of Administration, and many other positions during a 19-year tenure. “I missed that sense of community, that relationship building that goes on when you’re part of a team.”

So Hatiras eventually put the word out to executive search firms that he would be interested in returning to that realm. But there were some caveats, or conditions under which he would like to do so, he told HCN, adding that he set out what he called a “profile.”

The institution in question had to be in a good location, preferably the Northeast, he explained, adding that he preferred a community hospital with 200 to 300 beds in a small to mid-sized community (the situation at HUMC), and one with a good staff and a reputation for quality. The facility also had to be in “good shape,” which in this case meant the soundness of both the physical plant and the fiscal bottom line.

“I didn’t want to walk into a dire situation — I’ve been involved in those, and while it’s rewarding when you can pull out of one, I didn’t want to get back in a situation where, from day one, you’re struggling to keep your head above water,” he said, adding that one institution he was asked to consider could check all those boxes and thus fit that profile — Holyoke Medical Center, which was seeking a successor to Hank Porten, who announced he was stepping down after nearly 30 years at the helm of that facility.

Fast-forwarding a little, Hatiras eventually prevailed in a nationwide search for HMC’s new director; he is slated to start in early September. He spoke with HCN late last month about why he chose to accept this challenge at this stage of his career, while also touching on the challenges moving forward — for all community hospitals, and especially HMC.

At the top of that list is fiscal stability, he said, noting that ‘survival’ is too strong a word for a facility that is in decent condition financially, but still must fight for every dollar in reimbursements from payers and aid from the Commonwealth.

“This is simply a hospital that needs to keep its eye on the ball,” said Hatiras, noting that HMC is what’s called a “safety-net hospital” in Massachusetts, one that receives a combination of state and federal assistance to offset the large amount of free care that such facilities provide; Mercy Medical Center is also one. “We need to make sure we don’t miss an opportunity when it comes to grant money and other programs.”

There are other matters to contend with, such as updating a long-term strategic plan for the facility, and also improving visibility and awareness of a medical center that has a solid reputation and many quality programs, but remains too much of an unknown quantity in this region.

“What I’ve heard loud and clear from everybody is that we do a lot of great things here — we’re the number-one stroke center in the state of Massachusetts for performance, and we have a lot of other great programs — but folks here think we don’t put it out to the community enough, and people don’t know about them,” he explained. “We need to figure out a way to get the message out, because if you do wonderful things and no one knows about them, you can’t get the recognition and the patients you need.”

Background — Check

Hatiras told HCN that, unlike many hospital administrators today, he started out in direct patient care, as a physical therapist.

“I remember my first day on the job at St. Mary, which is what the hospital was called before it became University of Hoboken Medical School,” he said. “I got yelled at by the head nurse because, after I was finished with a patient, I left the bed rail down, and she was concerned about the patient falling out of bed.

“This gives me a good perspective; I’ve treated patients, I know what pain is like, especially in physical therapy, and know from a staff’s perspective what it takes every day to take care of patients,” he continued, referring to the many career stops he’s made and titles he’s held, ranging from corporate director of Rehabilitative Services to vice president of Post-Acute, Ancillary, and Support Services. “I started with patient care at the bedside, I’ve done home care, I’ve done nursing care and rehab — and my management style reflects all this. I’m easygoing, I can establish a rapport with patients and staff easily, and I’m personable. I like to walk around and talk to people, eat in the cafeteria, and chat with people; my door is always open.”

And at HMC, that door will be in the hospital, he went on, noting that Porten moved to what was supposed to be a temporary office in another building on the medical center’s campus during an extensive renovation and expansion project undertaken in the late ’90s, but that move turned out to be permanent.

“I’ll find space — I don’t care if it’s in a closet,” he explained. “For me, it’s very important for physicians, employees, and managers to easily access me, and for me to be close to patient-care areas.”

This is how it was at HUMC, which Hatiras led through a situation that could only be described as dire. Indeed, during his tenure, and while transitioning the hospital from municipal to private ownership, he implemented fiscal controls that resulted in a 50{06cf2b9696b159f874511d23dbc893eb1ac83014175ed30550cfff22781411e5} reduction in operating losses, from a $22 million loss in FY 2008 to $11 million in FY 2009. He also achieved a balanced budget the next year, without a reduction in force, by negotiating concessions with employees, physicians, and vendors, which resulted in savings of more than $15 million for two years.

Other accomplishments at HUMC include implementation of an electronic-medical-records system, creation of a hospitalist program, and the securing of a number of grants for operational and infrastructure improvements.

The challenges at HMC will be different, as most all of the above, including financial stability, has been achieved. Looking ahead, he said, beyond finding space for his office, the immediate priorities are to meet with a host of constituencies — physicians, employees, the board of directors, business leaders, and Holyoke city officials — to get a better feel for how well the facility is serving the community, and where change and improvement is needed.

Hatiras said he’s already met with a number of employees and physicians during a few visits to the medical center for interviews, and a few others after he was hired. He came away impressed with the long tenures of many of those he met, but also somewhat intimidated by the notion that many will be retiring within the next decade or two.

“The longevity here is amazing,” he noted. “It seemed like everyone I met said they’d been here 30 years or more. That’s fantastic, but it’s also a challenge; we have to make sure we have good people to follow. That’s something we have to plan for.”

Let’s Get Fiscal

While he won’t have to contend with mass retirements any time soon, there are some matters that will need more immediate attention.

At or near the top of that list is being ready as a community hospital for what is still in many respects an uncertain future in the healthcare industry.

“This is a big unknown — I think healthcare reform is not done with us yet, not by a longshot,” he said, referring to payment reform — specifically, paying providers to keep people healthy, not just for treating them when they’re sick — and other issues. “Is there a formula under which community hospitals can survive? I think there is. I’m not of the opinion that you have to merge with someone or be affiliated with someone to survive, but it’s not an easy road, either.

“If you work with your community, if you work with your physicians, and if we’re heading in the direction of payment reform and population health, then I believe community hospitals have a better chance of leveling the playing field,” he continued. “If it continues to be simply a volume game in the future and a rates game, then that’s a harder game to win; the bigger hospitals get the bigger volumes, and they get the higher rates from private payers.”

Another issue moving forward is raising HMC’s profile in the region, he said, adding that this is a big part of the challenge of changing the perceptions, and habits, of people who believe they can get better care in Springfield, Hartford, or Boston than they can in Holyoke.

It’s a situation Hatiras said he faced in New Jersey, when he assumed management of the rehabilitation hospital within St. Francis Hospital (part of the Franciscan Health System of New Jersey), which operated in the shadow, figuratively and almost literally, of the Kessler Institute for Rehabilitation, known for treating Christopher Reeve, among countless others.

“When they needed rehab, people automatically assumed that the best place to go, and the only place to go, was Kessler,” he said. “Here we were, the new kid on the block trying to attract those patients, and they would literally travel from our community 15 or 20 miles to the Kessler facility.

“Changing people’s perceptions is a lot of hard work,” he continued. “It’s relationship building, word-of-mouth referrals, and you have to make sure that people have a good experience and people feel good enough about it to tell others.”

At St. Francis, administration and staff did a lot of what Hatiras called “legwork,” which included everything from providing high-quality care to making sure that physicians in that area were aware of the outcomes, and that they were comparable, or better, than Kessler’s.

“That’s really the only way you can do it,” he went on. “Yes, you can put up a billboard, and you can put an ad in the paper — and those are necessary too — but the best advertisement, and the best marketing, is when people say, ‘I had a great outcome, the people were nice, I was in and out, I had a great experience.’”

Moving forward, HMC will try to use similar legwork, and perhaps some of those advertising vehicles, to make it known that it has a lot going for it, said Hatiras, from a location right off I-91 to a strong track record with regard to outcomes.

“We want to be the place for the immediate community, the neighborhoods right around the hospital,” he said, “but we also want to be the place for the people who choose to come here, because they’ve seen something good about it or heard something good about it, not just because they live next door. There is a lot to build on here.”

At Home with the Idea

In a month or so, Hatiras will no longer be homesick.

Instead, he’ll be home, in hospital administration, and presumably in an office in the main building at HMC not carved out of a closet.

As he talked with HCN about the type of scenario he desired as he returned to hospital management, he said he didn’t want a dire situation, but certainly did covet a challenge.

“I get easily bored with routine,” he said with a laugh. “I need spice in my life. Healthcare in general provides enough of that, but if you’re in a small place that needs to fight for every dollar, that usually provides a little more spice.”

And that’s one more reason why HMC fit his ‘profile,’ and is now the next line on his résumé.

Comments are closed.