Shock to the System – Deep Brain Stimulation Changes Lives of Patients with Tremors

Paul Schafer pressed a button on a small, handheld device, and started to shake.

The tremors were subtle at first, but within seconds his hands were shaking uncontrollably. When he picked up a plastic cup, the doctors sitting with him were grateful it was empty. When they handed him a pen to write his name, the scrawl couldn’t even be recognized as letters, let alone anything intelligible.

That was his life before his recent brain surgery, one of the first of its kind in the region. But when he pressed that button again — not without difficulty — the shaking stopped, and he was able, once again, to perform those simple activities.

That’s his life now.

“It changed my whole life,” said Schafer, 74, while sitting with his wife, Kathie, and the Baystate Medical Center doctors who facilitated that change. “All the mundane things you do every day, I wasn’t able to do without help — drink coffee out of a mug, brush my teeth, comb my hair, button my shirt … all the stuff everyone takes for granted. It was too challenging to do those things before the surgery.”

The procedure is known as deep brain stimulation, and it helps people like Schafer — who suffers from a common neurological movement disorder called essential tremor — as well as patients with Parkinson’s disease, dystonia, and obsessive-compulsive disorder, a chance at a normal life.

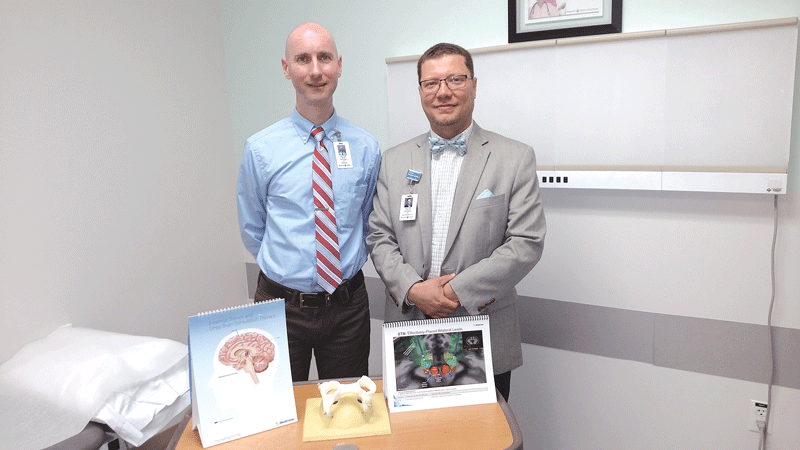

The tremors caused by such conditions can be debilitating. But DBS, performed successfully — as Baystate neurosurgeon Dr. Mohamad Khaled did for Schafer — is opening up a dramatic new door to quality of life for potentially millions of sufferers.

The surgery — which involves drilling a small hole into the skull, under local sedation, and inserting electrical wires into the area of the brain where circuit errors are causing the tremors — may also hold potential in areas ranging from Alzheimer’s disease to severe depression, but those frontiers are still being studied.

“Paul had symptoms for 15 years, and took a number of medications with some response; then the symptoms progressed and really affected his life in a negative way,” he went on. “He had difficulty using his hands — writing, holding a cup of coffee without spilling it, using a fork and knife to eat, brushing his teeth.”

Because the medications weren’t working anymore, the Schafers saw DBS as, well, a no-brainer.

“Dr. Adam was suggested by Paul’s previous neurologist, who said there may be something else we could look into,” said Kathie Schafer. “When we walked out of the building, we sat in the car, looked at each other, gave a big sigh, smiled, and said, ‘it looks like there’s a way — a better way of life.’ I think that was how we thought about the entire procedure.”

Finding the Sweet Spot

According to the National Parkinson Foundation, deep brain stimulation has proven to be an effective treatment for that disease’s symptoms, such as tremor, rigidity, stiffness, slowed movement, and walking problems, as well as similar symptoms present in essential tremor.

DBS does not damage healthy brain tissue by destroying nerve cells, the foundation noted. Instead, it uses a surgically implanted, battery-operated medical device called a neurostimulator to deliver electrical stimulation to targeted areas in the brain that control movement, blocking the abnormal nerve signals that cause tremors.

The DBS system consists of three components: the ‘lead,’ an electrode — a thin, insulated wire — inserted through a small opening in the skull and implanted in the brain; another insulated wire passed under the skin of the head, neck, and shoulder, connecting the lead to the neurostimulator; and the neurostimulator itself, a sort of battery pack implanted under the skin, usually near the collarbone.

In the first phase of the procedure — called phase zero, because it doesn’t involve surgery — the neurosurgeon uses MRI or CT scanning to identify the area of the brain where the electrical nerve signals generate the tremors.

Phase one, as the next step is known, involves implanting the electrodes in the brain while the patient is under sedation. When the patient wakes up, Khaled asks him to point a laser at a target on the wall. As the doctor adjusts the electrical wires to target the appropriate circuit in the brain, the patient’s shaking hand slowly begins to stop shaking so that the laser is directly pointed in one location. That’s when Khaled knows he’s found the ‘sweet spot’ for the electrodes, and the patient suddenly is nearly cured of the tremors.

“The circuitry is in disarray, so you sort of shut that circuit down,” he explained. “Sometimes it’s like a radio dial — you need to dial it up or tune it down.”

After a few weeks of healing, a second surgical procedure is completed to make the changes permanent. The wires are attached to a device implanted in the chest, which is programmed to send electrical impulses to the brain, which block the signals causing the tremors.

Not everyone with essential tremor or Parkinson’s is a candidate for deep brain stimulation, Adam explained. The best candidates have suffered from tremors for a long time and failed to find relief through medications, and the tremors have to be severe enough to impact their daily life in a significant way. “If those conditions are met, we consider surgery to treat them.”

That said, only about 10{06cf2b9696b159f874511d23dbc893eb1ac83014175ed30550cfff22781411e5} of patients with essential tremor are good candidates, and 20{06cf2b9696b159f874511d23dbc893eb1ac83014175ed30550cfff22781411e5} of those with Parkinson’s, though the calculation with Parkinson’s is a bit more complex, requiring at least some positive response to medications and a lack of other conditions, such as dementia, cognitive issues, and severe depression.

About 100,000 patients worldwide have undergone DBS since 1997. Previously, the closest hospitals in the Northeast that offered it are in Boston to the east, Albany, N.Y. to the west, Burlington, Vt. to the north, and New Haven, Conn. to the south. “So we had a big hole in the middle,” Khaled said.

That’s important, Adam noted, because patients with essential tremor or Parkinson’s are often unable to drive and may not have access to transportation, and the procedure is more than the surgical visits; many appointments are necessary in advance of the actual surgery. “Having it here makes it available to a lot of patients who would not have access to it otherwise.”

In Schafer’s case, he had hit the wall with medications; there was nothing else he could try. Despite the risks possible with any surgery, “I was very positive about the whole procedure.”

Still, the risks were minimal, Adam explained. In any brain surgery, the risk of bleeding or stroke is about 2{06cf2b9696b159f874511d23dbc893eb1ac83014175ed30550cfff22781411e5}, and the risk of infection between 3{06cf2b9696b159f874511d23dbc893eb1ac83014175ed30550cfff22781411e5} and 5{06cf2b9696b159f874511d23dbc893eb1ac83014175ed30550cfff22781411e5}. “That’s pretty low. Ninety-five percent of the time, nothing happens. And this does not carry any extra risk compared to other brain surgeries; in fact, there’s less. The level of invasiveness is less. The electrodes are thinner than a spaghetti noodle.”

Science, Not Fiction

Schafer was also, naturally, curious about how long DBS would prove effective. Khaled and Adam explained that early response is always the strongest, and over time — perhaps a decade or more — some of the effect may start wearing off. But the device settings can be fine-tuned to provide better coverage and more control.

In a Parkinson’s patient, the surgery’s effectiveness lasts between six and 10 years on average, but that disease’s symptoms are not limited to tremors, and those other symptoms progress regardless of the surgery. “So the management changes a bit,” Khaled said, “but studies show that quality of life with surgery is better than for those without surgery — that is, for the right candidates.”

Schafer knew he was one of those success stories when, right after the electrode began delivering signals to his brain, doctors handed him a flashlight, which he slowly — and accurately — lifted up to his mouth like a glass.

“We had tears in our eyes,” he said. “I wouldn’t have been able to do that with one hand.”

He shuts the system down to sleep — “when I turn it off, it’s a whole different world,” he noted — but restarts it in the morning and feels the tremors subside. He compares the feeling, when the neurostimulator switches on, to the tingle of a Novocaine shot, only throughout his whole body.

Today, he and Kathie say they understood both the potential and the risks — and there was really never any question.

“Of course, it does get a little scary, the idea that Dr. Khaled would drill into my husband’s head, but it needed to be done,” she said. “If there was a chance Paul could have a better quality of life going forward, then we were both very willing to give this a try.”

She’s glad they did, saying they’ve felt “nothing but happiness and wonderful excitement” as Paul rediscovered the ability to perform the tasks of everyday life with no difficulty. “We just keep smiling. It’s not without its risks or challenges, but to us, it was like something out of Star Wars. It was a miracle.”

Paul, now able to live a relatively normal life, plans to start a support group for people with essential tremor. “There are a lot of people out there with what I have,” he said, knowing that he can both share his experiences with those who might qualify for the surgery and at least bring together those who don’t. But he hopes more people fall into the former category than the latter.

“This has changed my life,” he said. “I strongly advocate getting the surgery done if you qualify for it. It makes so much difference.”

Kathie agrees. “He has a wonderful sense of humor, and he’s always been able to accept what happened with him and take it humorously and have everyone relax around him. But I knew it bothered him,” she said.

After letting Khaled, as she put it, drill into her husband’s head, “it’s made him 10 to 15 years younger in his attitude because now he goes out fully, completely aware of the fact that he can do whatever he wants to do, whenever he wants to do it.”

Comments are closed.