Vaccinating Massachusetts Is a Thorny, Complicated Challenge

Arms Race

By Joseph Bednar

Back in December, the news was all good. COVID-19 vaccines developed by Pfizer and Moderna earned emergency-use approval, and shipments rolled out to all 50 states, which then began distributing them to the first priority group: frontline healthcare workers.

“This vaccine makes me feel excited,” Amy Hamel, Emergency Department nurse case manager at Cooley Dickinson Hospital, said back then. “Relief is in sight — for primary-care offices, for nursing homes, for daughters taking care of elderly mothers.”

Hamel not only gave her co-workers shots, she wrote messages on their arms to mark the moment when vaccines finally arrived in Northampton.

On the arm of registered nurse Nick Hebert, a Marine Corps veteran who works in the Respiratory Illness Clinic, the Band-Aid that partially obscured a tattoo of the globe read, “for the world.”

“This vaccine is important for public safety,” Hebert said. “I feel I am helping the rest of the community by getting vaccinated.”

That remains true, of course, but as the weeks have rolled on, a pair of competing challenges have arisen. One is making sure everyone who wants a vaccine — and is authorized to do so by the state’s phased priority list (more on that later) — gets one, a process that has been riddled with long waits at mass-vaccination sites, difficulty securing appointments at smaller sites, and confusion when navigating the online registration process.

The other challenge, healthcare professionals say, is helping people who may be reluctant to understand the benefits of vaccines. Those two challenges may seem contradictory at a time when it’s tough for even enthusiastic people to access the vaccine, but they’re really not — because the rollout is expected to last several more months, and every point along that journey matters when it comes to building herd immunity in Massachusetts.

“We recognize it’s a journey, and folks might not feel comfortable with it today, but maybe you’ll feel comfortable tomorrow,” said Lindsey Tucker, associate commissioner of the Massachusetts Department of Public Health (DPH). “We want to be sure that, when you’re eligible for the vaccine, you can access it when you’re ready for it.”

Tucker said those words during a webinar held earlier this month by the Public Health Institute of Western Massachusetts, which also featured input from state Sen. Eric Lesser and Dr. Sarah Haessler, lead epidemiologist and infectious-disease specialist at Baystate Health, who has emerged as a leading local voice in public information around COVID-19.

Haessler detailed the amount of data that emerged from clinical trials for the vaccines, and noted that the FDA will approve one only if the expected benefits outweigh potential risks.

“We recognize it’s a journey, and folks might not feel comfortable with it today, but maybe you’ll feel comfortable tomorrow. We want to be sure that, when you’re eligible for the vaccine, you can access it when you’re ready for it.”

“The FDA reviewed all the data — it’s pages and pages and pages of data — around every single thing they did in these clinical trials to be sure of the safety and efficacy of the vaccination,” she said, noting that multiple mechanisms are currently in place to track instances of side effects.

While significant side effects are rare — anaphylaxis is one, which is why individuals receiving the shots must remain at the vaccination site for 15 to 30 minutes — most people experience nothing more than arm soreness, fever, chills, tiredness, and headache; most symptoms fade after a day or two, although they last longer in rare cases. Many people feel no effects at all.

“It’s certainly a lot safer to get the vaccine knowing there are just minor side effects than to take your chances getting infected with COVID-19,” Haessler added. “The more people we vaccinate, the closer we get to herd immunity, and the closer we get to going back to life, where we can see our family and friends and return to pre-pandemic activity.”

The Next Phase

After prioritizing specific groups of people in phase 1 of the vaccination rollout — including healthcare workers, first responders, and residents of long-term-care facilities, assisted-living centers, and congregate care — Massachusetts has been in phase 2 for most of February.

Newly eligible groups include individuals 65 and over, including residents and staff of low-income and affordable public and private senior housing, and individuals age 16 and older with two or more co-morbidities, from a list that includes asthma, cancer, chronic kidney disease, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, Down syndrome, certain heart conditions, weakened immune system from solid organ transplant, obesity, pregnancy, sickle-cell disease, smoking, and type-2 diabetes.

Later in phase 2, access will roll out to workers in the fields of education, transit, grocery stores, utilities, agriculture, public works, and public health, as well as individuals with one co-morbidity. Phase 3, expected to begin in April, will include everyone else.

Demand, as noted, is high. Even for the groups recently given the green light in phase 2, it could take more than a month for all eligible individuals to secure an available appointment unless federal supply significantly increases, Gov. Charlie Baker noted. Recently, Massachusetts has been receiving approximately 110,000 first doses per week from the federal government, and residents are encouraged to keep checking the state website as appointments are added on a rolling basis.

“This has been a hard year for everyone, but I do think there is light at the end of the tunnel as we see the vaccines do work,” Lesser said at the webinar. “The key challenge is making sure the vaccine is distributed in an equitable and speedy way, and certainly that our communities in Western Mass. are not left out of that.”

One change he and other legislators pushed for was to allow individuals unable to access the internet to call the state’s 211 information number and follow the prompts to make vaccine appointments by phone.

“Focusing only on an online system doesn’t work; we need a phone option,” he said, noting that a ‘digital divide’ exists for many older, poorer, or rural residents. Also, “we need to dramatically simplify the website. There are too many links, too many places people have to navigate to find out where to go.”

Lesser would also like to see more local and even mobile options people can access. “The state’s approach has been to bring people to the vaccine, but we need to be deliberate about the mindset of bringing the vaccine to the people,” he said. “There are a lot of things we can’t control — we are at the mercy of the federal government with the number of doses — but we can control how we distribute them and how we get them into people’s arms.”

Earlier this month, during the Massachusetts Medical Society’s monthly COVID-19 conference call with DPH physicians, Dr. Kevin Cranston, assistant commissioner and director of the Bureau of Infectious Disease and Laboratory Sciences, said individuals with two or more co-morbidities will not have to prove those conditions in any way, as the system essentially operates by self-attestation.

“We’re not asking patients to go back to their clinicians, their primary-care providers, for medical evidence, and we’re not asking physicians to make clinical judgments,” he noted.

State Epidemiologist Dr. Catherine Brown also talked about the DPH’s public vaccine-confidence campaign.

“The campaign recognizes that there are particular populations, especially people of color and other minority populations, that may have understandable increased concern about receiving the vaccine,” Brown said, noting that Public Health Commissioner Dr. Monica Bharel considers health equity to be a primary priority. “Therefore, DPH is having additional, ongoing conversations about the best ways to try to improve vaccine confidence among some of these groups that are harder to reach.”

Rolling Up Their Sleeves

Judging by the demand, most people seem enthusiastic about the vaccine, particularly those who work in healthcare.

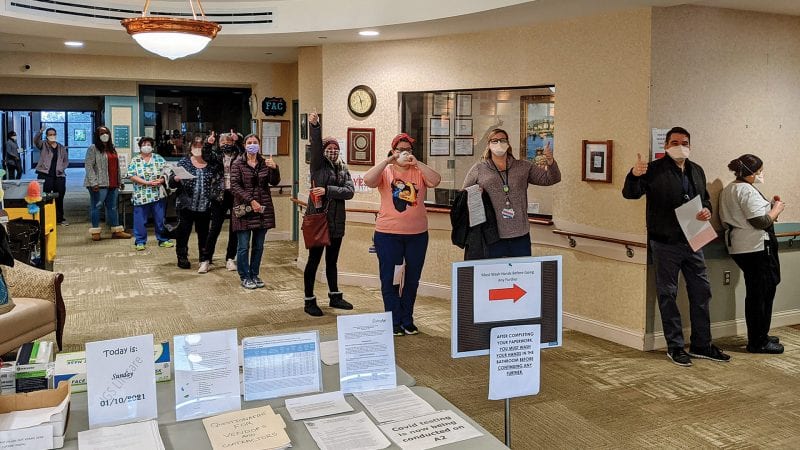

“Taking the vaccine is the best solution to reducing the risk of spreading the virus,” said Shannon Wesson, director of Nursing at the Leavitt Family Jewish Home during a vaccination event for residents and staff in January. “I don’t want to risk giving it to a resident, or to anyone. If I can be a part of the solution, I want to be.”

Uvalyn Davis, a CNA who has been working at the facility for more than 23 years, contracted the virus back in April, and still feels the physical effects of the illness. “I am so excited to get the vaccine,” she said. “I want to be able to get my strength back and not wear a mask. I want to hug my residents and dance with them again. I know what I went through, and I don’t want to get COVID again. The vaccine is for our safety, we’re all here together, and it is the best thing we can do.”

What it isn’t, Haessler said, is a license to stop doing the things that slow the viral spread. It takes about 10 days for someone to begin developing immunity after the first dose, and full protection doesn’t arrive until about 14 days after the second dose. But it’s still unknown how easily vaccinated individuals can spread the virus to others.

“The bottom line is, even though you’re vaccinated, you still need to wear a mask, stay six feet apart, avoid crowds, and wash your hands frequently,” she explained, noting that vaccination is the last layer of protection, but far from the only one.

It is, of course, a critical one, and that’s a message she continues to spread to those who might be anxious about making an appointment.

“Educate yourself about vaccine safety and talk to trusted sources — your own personal healthcare provider as well as people you know who have been vaccinated,” Haessler said. “Many, many healthcare workers in our community are vaccinated now because we went first.

“I think a lot of our healthcare workers were anxious at first, but as they saw their colleagues getting the vaccine and doing fine with it, they were excited, because now there’s a light at the end of the tunnel — there’s some hope that helped bolster confidence in it,” she went on. “The more we know about this, the more people will feel comfortable with it. Knowledge is power.”

So is hope, said Dr. Bobby Redwood, chief of Emergency Medicine at Cooley Dickinson.

“For me, this was a personal milestone,” he said when he was part of the first wave to get vaccinated locally. “This is a service to our community, to my family, and ultimately to the world. And this a pattern I hope we see spread like wildfire, because the more people who get vaccinated, the quicker we will get out of this pandemic.”