Mounting Problem Some Collective Thoughts on Hoarding

Most people have objects they have saved far beyond the point where they are useful. But few understand why someone would collect and save so much that it takes over their home to the point where they are unable to cook, sleep in their bed, or even use their bathroom.

But that’s exactly what occurs when someone has compulsive hoarding disorder. “Almost everyone has some trouble throwing things away, but there are people who can’t throw away anything,” said Benjamin Liptzin, chairman of the department of Psychiatry at Baystate Medical Center.

The TV show Hoarders offers stories about these individuals and their attempts to recover from a condition that can interfere with their safety and ability to live normally. And many people have heard about the Collyer brothers, Langley and Homer, who were found buried under mountains of debris that packed their 12-room mansion in New York City.

For these people and many others, the compulsion to take things home and keep them far exceeds the realm of normalcy. The disorder results in health and fire hazards and social stigma, because people who hoard cannot invite guests into their homes.

But there are reasons for their behavior.

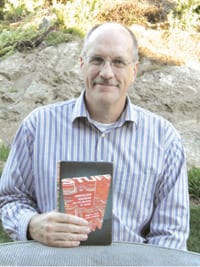

Randy Frost, one of the eminent researchers in the U.S. studying the disorder and co-author of Stuff: Compulsive Hoarding and the Meaning of Things, says the reason it is so difficult for these people to relinquish possessions is that everything they save has real significance to them. In some cases, such as a journalist who collects newspapers, the collection is a concrete embodiment of their professional identification.

“So getting rid of them makes the person feel as if they are losing that piece of themselves,” said the Harold Edward and Elsa Siipola Israel professor of Psychology at Smith College. When people hoard newspapers or magazines, the reason is because they want to make sure they don’t lose the information in them, because they perceive it as valuable.

But the majority of items hoarders save are due to the way they see things. “People with this disorder view objects very differently than the rest of us,” Frost said, using the example of a bottle cap. Although most people think of it as trash, “people who hoard pay attention to the shape, color, texture, and appearance of things. There is so much complexity to their thought about the object, it pushes everything else out of their consciousness. And once they note those things, they begin to elaborate about how they could use it.”

For example, they might think about using the bottle cap as part of a collage, after noticing the grooves on its side and other finite details. “Then it becomes even harder to get rid of it,” Frost said, adding that items become so valuable in the person’s mind that he or she will purchase them whether or not they can afford to, which can lead to bankruptcy, among other problems. And the items they collect very seldom fall into one category.

Signs and Symptoms

No one becomes a hoarder overnight, but signs of the disease do surface decades before it becomes an issue. “Most children have a favorite doll or toy they hang onto, and we don’t worry about it unless their collecting gets to be obsessive,” Liptzin said. “But hoarding usually starts slowly.”

Research shows the behavior typically begins between the ages of 13 and 15, although it doesn’t become problematic for a decade or more. There appears to be a genetic component to the disorder, which ranges from mild to severe, and some studies show that chromosomes may be involved. “In many cases it looks like crazy behavior, but it is no different than the reasons we all use when we save things. People who hoard just apply the reasons to more things,” Frost said.

Christopher Overtree, director of the Psychological Services Center at UMass Amherst, says the condition is a biological illness related to how the brain processes information. “And in each small circumstance when the person has to make a choice of whether to save or discard something, they usually save it because keeping it doesn’t produce anxiety,” he explained.

Studies show that people who hoard are highly intelligent, which accounts for the complexity of their thinking. But half of them are clinically depressed, and a large percentage have attention deficit disorder with hyperactivity, which researchers think is related to their inability to organize their possessions.

“They are easily distracted and have difficulty staying on task and also have a problem with categorization,” Frost said, explaining that, when most people get an electric bill, they put it with other bills, while hoarders organize their world visually and spatially. “They may put the bill on a pile to the left, and when they want to find it, they have to remember where it is. They create a map in their head and know, as they put other things on top of it, that the bill is about a foot down in the pile.”

But their mental map is not very accurate, and if someone else in their home moves the bill, it destroys their map.

In the past, drugs used to treat anxiety or depression were often prescribed to treat hoarding. “But usually the best treatment is a combination of drugs and behavioral therapy. The fact that the person has some insight is part of the motivation to seek treatment, and they usually can get somewhat better,” Liptzin said. “But the things they have collected which others might think are trivial have great emotional weight and value to them,” which makes recovery and relinquishing them difficult.

So difficult that Frost has seen people who have packed an entire house with their possessions and had to move as a result or who have camped outside the home or become homeless as a result. But even if they lose their home, they may put everything in a storage unit and pay for it, even if they can’t afford a place to live, he told HCN.

“Help usually comes only after their living environment has created a concrete problem,” Overtree said, adding that elders who can’t navigate within their home due to hoarding are at risk of falling, and if a child is living with the person, the environment can be viewed as a form of neglect. “The consequences can be severe, but these people feel compelled to save things; it is not something that is really under their control,” he said.

In the past, the illness was thought to be a subtype of obsessive compulsive disorder, but as researchers learn more, they are finding it is unique, and there is a proposal to designate it as a separate disorder in the Diagnostical and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders.

Progressive Illness

Many people who end up as compulsive hoarders begin collecting one type of item. However, “collecting isn’t a sign of illness,” Liptzin said, adding that there are many people who collect art or other valuable items. And if they have plenty of money, even if they do fill a home with clutter, they sometimes purchase another house rather than get rid of any of it.

“These people never meet the criteria of hoarders because they can afford what they are doing,” he added. “But when collecting things takes over an entire house, it is clearly pathological.”

Overtree concurs. “To a certain extent, the problem is whether what they are saving exceeds the capacity of their home.”

But there are related consequences. Studies show people with the disorder are less likely to get married or stay married because spouses get fed up with the clutter, try to intervene, and the marriage ends, Frost said.

But the problem typically doesn’t become severe until people hit their 50s or 60s. It often gets worse when parents die and the hoarder must deal with their possessions as well. Overall, the disorder affects about 6{06cf2b9696b159f874511d23dbc893eb1ac83014175ed30550cfff22781411e5} of the population.

Experts agree that people with the disorder recognize they have a problem.”It becomes embarrassing, and there is some insight that it’s abnormal,” Liptzin said. But hoarders see opportunity in their possessions.

Frost had a client who collected recipes and recipe books with the dream of hosting dinner parties that her friends would rave about. Her husband left her early in their marriage, and she created the image “of the person she could be when she looked at the recipes, which had nothing to do with reality. There are a multitude of reasons why people save things,” he explained.

But since each object they save has emotional weight, thinking about getting rid of any of them makes the hoarder feel vulnerable and anxious. “So they try to avoid distress by keeping everything,” Frost said.

Liptzin had a patient who collected toys for her grandchildren, even though they had grown into adults. Many of them were in unopened packages, and “there was a part of her that knew it was unreasonable. But whenever she tried to get rid of them, she would become too anxious at the thought of letting them go,” he said.

Her husband lived with the problem for years, but as they grew older, he contacted the local VNA for help, and it called the health department. As a result, the woman was removed from the home.

“Hoarding clearly interferes with the person’s life as well as the lives of people close to them,” Liptzin said. “But it doesn’t help to get upset with them.”

Treatment Options

Frost said effective therapy teaches people to tolerate their urge to bring things home and also shows them that, if they do get rid of something, the loss will not haunt them.

He and his colleagues do this through a series of small experiments in which the person gives the therapist an item to keep for a week. “Then we ask them how many times they missed it or could have used it, and what that taught them about the object,” Frost said. But since most people don’t seek help until they are forced into it and the disorder is complex, progress is slow.

Overtree uses a technique he calls “motivational interviewing” which relies heavily on empathy and appreciation of the client’s perspective, as well as “a healthy dose of kindness and tolerance.” It differs from empathic listening, he said, in that the therapist has a goal in mind, which is to increase the client’s insight about the problem as well as their motivation to deal with it.

Family members often have been frustrated for decades as a result of their failed attempts to convince the person to get rid of belongings without success.

“But they see the problem differently than the person who is afflicted,” Overtree said. “The person who hoards is responding to an internal problem that has to do with decision making and their desire to save. Families often try to help by pressuring them, but that can make the problem worse or cause their loved one to withdraw. If you approach someone from an antagonistic standpoint, it tends to push them into a polarized position, whereas, if you approach them with empathy and respect, you may be able to access the part of them that sees the value of making positive changes.”

Although being forced into treatment is unpleasant, it can be helpful, as the pressure to change is not coming from the therapist. “And there is a lot of shame associated with hoarding. People may not have insight about the severity of the problem, but they are often embarrassed about having others come to their home,” Overtree said.

Frost explained that clutter is only a byproduct of the disorder, and researchers have not yet discovered what happens in the brain to cause it. However, he does teach therapists how to deal with clients who have the disorder and advises family members to visit the International Obsessive Compulsion Foundation at its Web site, www.ocfoundation.org, for more information.

Shift in Thinking

Overtree said that therapy must focus on adjusting the person’s thought process and their emotional reaction to getting rid of things. “People underestimate how tricky the condition is, and although the person needs a therapist, the therapist also needs a team.”

That should include loved ones, who need to learn to take a different approach and try to understand that every object the hoarder saves is extraordinary to them in a physical way the average person cannot comprehend.

Comments are closed.