We Are a Different Place – Shriners Hospitals for Children Continues to Broaden Its Reach

George Gorton recalls a conversation he had with the parent of a child who nearly drowned — and then required months of intensive rehabilitation to regain full function, both physically and mentally.

Unfortunately, the only two pediatric inpatient rehabilitation units in Massachusetts are located in Boston.

“There was nowhere in Western Massachusetts to bring him back to maximum function level,” Gorton told HCN. “She couldn’t transfer her family to live in Boston for two months to get the care she needed.”

That has changed, however, with last month’s opening of a new, 20-bed Inpatient Rehabilitation Unit at Shriners Hospitals for Children – Springfield.

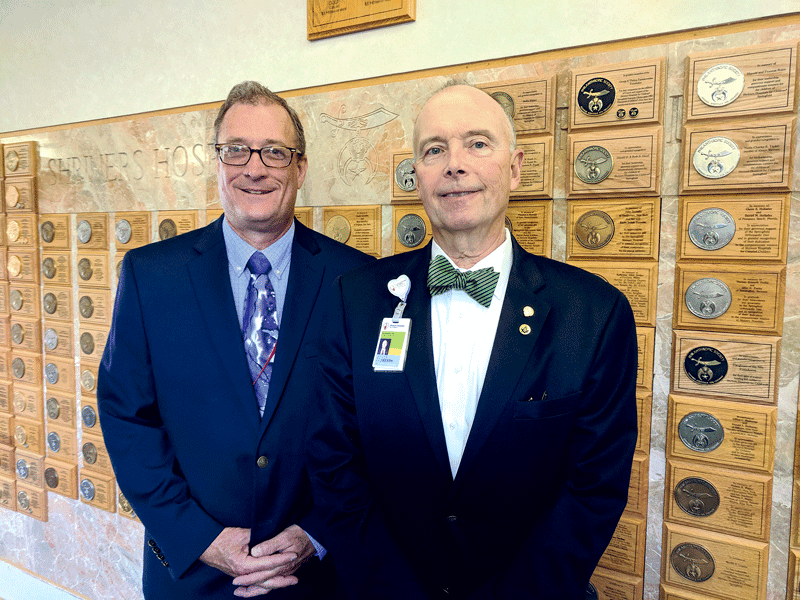

“Now, everyone in Western Massachusetts who needs that kind of support can come here rather than figure out how to maintain their family 90 miles away,” said Gorton, the hospital’s director of Research, Planning, and Business Development. “It made sense; we had this excess capacity and didn’t need to do a lot of renovation work. It seemed like a natural fit, so we worked to get it set up.”

That excess capacity is due to a trend, increasingly evident over the past two decades, toward more outpatient care at Shriners — and hospitals in general. But despite the space being in good shape, it still needed to be converted to a new use and outfitted with the latest equipment, and that necessitated a $1.25 million capital campaign, which wound up raising slightly more.

The new unit is an example of both the community support Shriners continues to accrue and the hospital’s continual evolution in services based on what needs emerge locally.

Specifically, Gorton said, the hospital conducts a community-needs assessment every three years, and out of the 2013 study — which analyzed market and health data and included interviews with primary-care providers and leaders in different healthcare sectors — came a determination that an inpatient pediatric rehab clinic would fill a gaping hole.

When H. Lee Kirk Jr. came on board as the facility’s administrator in 2015, he and his team honed that data further, spending the better part of that year reassessing the hospital’s vision and putting together a strategic plan. They determined that continued investment in core services — from neuromuscular care and cleft foot and palate to spine care and chest-wall conditions — was an obvious goal, but they also identified needs in other areas, from fracture care to sports medicine to pediatric urology, as well as the new rehabilitation unit.

“After a traumatic injury — a brain injury, serious orthopedic injury, it could be spinal injury — a child might have some functional deficits, even though they are not in a medically acute situation,” Kirk told HCN. “So they come to this program and spend anywhere from two to eight weeks with intensive rehabilitative services, which is physical therapy, occupational therapy, and speech therapy, and also physician care and nursing care.”

Under the supervision of a fellowship-trained pediatric physiatrist, patients admitted to the unit will receive a minimum of 15 hours of combined physical, occupational, and/or speech therapy per week, added Sheryl Moriarty, program director of the unit. “Using an individualized, developmental, and age-appropriate program model, our Inpatient Rehabilitation team will manage medically stable children and adolescents with a variety of life-altering and complex medical conditions.”

That evolution in services makes it even more clear, Gorton said, that the landscape is far different than it was in 2009, when the national Shriners organization seriously considered closing the Springfield hospital.

“We’re stronger in every sense of the word,” he said, “from our leadership to the quality of the employees we have to the diversity of programs we have to the financial strength behind all this. We are a different place.”

First Steps

When a boy named Bertram, from Augusta, Maine, made the trek with his family to Springfield in February 1925, he probably wasn’t thinking about making history. But he did just that, as the hospital’s very first patient.

“While Shriners opened hospitals primarily to take care of kids with polio, Bertram had club feet,” Kirk said — a condition that became one of the facility’s core services.

After the first Shriners Hospitals for Children site opened in 1922 in Shreveport, La., 10 other facilities followed in 1925 (there are now 22 facilities, all in the U.S. except for Mexico City and Montreal). Four of those hospitals, including one in Boston, focus on acute burn care, while the rest focus primarily on a mix of orthopedics and other types of pediatric care.

As an orthopedic specialty hospital, the Springfield facility has long focused on conditions ranging from scoliosis, cerebral palsy, and spina bifida to club foot, chest-wall deformities, cleft lip and palate, and a host of other conditions afflicting the limbs, joints, bones, and extremities. But that’s the tip of the proverbial iceberg.

“There’s some consistency in services, but each of the hospitals has adapted to the needs that present themselves in that community,” he went on, noting specialties like rheumatology, urology, and fracture care in Springfield, as well as a sports health and medicine program that brought on two athletic trainers and is currently recruiting a pediatric orthopedic surgeon with training in sports medicine.

“This is along the lines of a community service, and our athletic trainers are working with school systems and private sports clubs in the community, to participate from a preventive point of view, but they certainly can attend games as a first responder and then follow up with treatment.”

In all, more than 90{06cf2b9696b159f874511d23dbc893eb1ac83014175ed30550cfff22781411e5} of care provided in Springfield is outpatient, reflecting a broader trend in healthcare, Kirk added. “We have always had, and still have, the only pediatric orthopedic surgeons in Western Massachusetts.”

After its clinical work, he noted, the second part of the Shriners mission is education. Over the past 30 years, thousands of physicians have undertaken residency education or postgraduate fellowships at the children’s hospitals.

“We have a lot of students here in a lot of healthcare disciplines, particularly two orthopedic residents who come on 10- to 12-week rotations from Boston University and Albany Medical Center. We have nursing students, nurse practitioners, physical and occupational therapists — a whole cadre of individuals.”

The third component of the mission is research, specifically clinical research in terms of how to improve the processes of delivering care to children. That often takes the shape of new technology, from computerized 3D modeling for cleft-palate surgery to the hospital’s motion-analysis laboratory, where an array of infrared cameras examine how a child walks and converts that data to a 3D model that gives doctors all they need to know about a child’s progress.

More recently, a capital campaign raised just under $1 million to install the EOS Imaging System, Nobel Prize-winning X-ray technology that exists nowhere else in Western Mass. or the Hartford area, which enhances imaging while reducing the patient’s exposure to radiation.

That’s important, Kirk said, particularly for children who have had scoliosis or other orthopedic conditions, and start having X-rays early on their lives and continue them throughout adolescence.

It’s gratifying, he added, to do all this in a facility decked out in child-friendly playscapes and colorful, kid-oriented sculptures and artwork.

“It’s truly a children’s hospital when you look around the waiting areas and the lobbies,” Kirk said, noting that ‘child-friendly’ goes well beyond décor, to the ways in which the medical team interacts with patients. “This is a happy place, and it’s a privilege for me to be part of such a mission-driven organization. I’ve been in this business for 35 years, and this is the most mission-driven healthcare organization I’ve ever been associated with — and I think others feel that way too.”

Joint Efforts

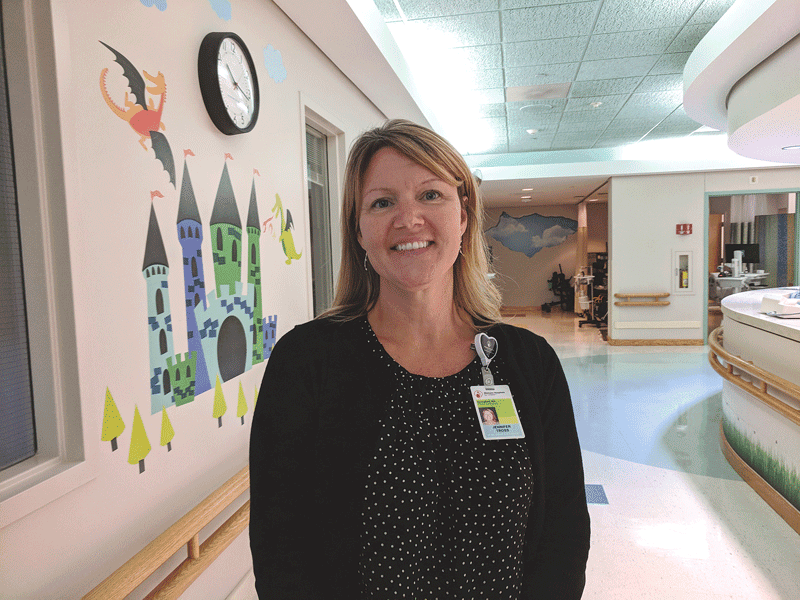

Jennifer Tross certainly does. She’s one of the newest team members, coming on board as Marketing and Communications manager earlier this summer. “I felt the commitment as I was being recruited here,” she said. “It’s an honor to be a part of it, really.”

It’s not that difficult to uphold the hospital’s mission when one sees the results, Kirk added.

“Our vision is to be the best at transforming the lives of children and families, and that’s what we look for every single day,” he told HCN. “You see how their lives are transformed, and how, regardless of their situation, they’re treated like normal kids here. That helps them to evolve and have confidence to function normally at home, at school, and in their communities.”

There’s a confidence in the voices of the hospital’s leaders that wasn’t there nine years ago, following a stunning announcement by the national Shriners organization that it was considering closing six of its 22 children’s hospitals across the country — including the one on Carew Street.

In the end, after a deluge of very vocal outrage and support by families of patients and community leaders, the Shriners board decided against closing any of its specialty children’s hospitals, even though the organization had been struggling — at the height of the Great Recession — to provide its traditionally free care given rising costs and a shrinking endowment.

To make it possible to keep the facilities open, in 2011, Shriners — for the first time in its nearly century-long history — started accepting third-party payments from private insurance and government payers such as Medicaid when possible, although free care is still provided to all patients without the means to pay, and the hospital continues to accommodate families who can’t afford the co-pays and deductibles that are now required by many insurance plans.

“That was a very good strategic move,” Kirk said, noting that, regardless of the change, 65{06cf2b9696b159f874511d23dbc893eb1ac83014175ed30550cfff22781411e5} of the care provided last year to 11,501 children was paid for by donors, the Shriners organization, and system proceeds.

If a family can’t pay, he noted, the hospital does not chase the money, relying on an assistance resource funded by Shriners and their families nationwide. “One of the largest causes of personal bankruptcy is healthcare. It’s unfortunate that all healthcare can’t be delivered in the Shriners model. But I don’t disparage my colleagues — they don’t have a million-plus Shriners and their families around the world who are incredibly passionate about raising money to take care of kids.”

As a result of this model, “Shriners Hospitals for Children is a net $10 billion business with no debt. And one of the things we try to minimize is the support we require from system proceeds, other than our endowment,” he noted. “And we’ve been very successful here. It’s kind of an internal competition — which hospital requires the least support from the system.”

In the past three years, the Springfield facility has ranked second on that list twice, and third once. And that’s despite actually growing its services significantly. In 2016, Gorton said, the hospital grew its new patient intakes by 44{06cf2b9696b159f874511d23dbc893eb1ac83014175ed30550cfff22781411e5}, followed by 26{06cf2b9696b159f874511d23dbc893eb1ac83014175ed30550cfff22781411e5} the following year and a projected 20{06cf2b9696b159f874511d23dbc893eb1ac83014175ed30550cfff22781411e5} this year. “So we serve a lot more children across the diverse set of services we provide.”

He noted that the outpouring of community support in 2009 — which included a sizable rally across the street — was an awakening of sorts.

“They said, ‘hell no, don’t go, we need you; stay here,’” he recalled. “Since then, we’ve done everything we could to identify what it was that the community wanted from us and recreate ourselves in that image. I think we’ve been largely — more than largely … exceptionally — successful on that.”

The hospital saw a lot of turnover in the years following 2009, Gorton added, “but the people who stayed are committed to the mission and vision of transforming children’s lives. The people who have joined us since then sense that the one thing we don’t compromise on is our mission and our vision.”

Best Foot Forward

When asked where the hospital goes from here, Kirk had a simple answer: Taking care of more children.

That means making sure area pediatricians, orthopedists, and hospitals are aware of what Shriners does, but it also means bolstering telehealth technology that allows the hospital not only to consult with, say, burn experts at the Boston facility, but to broaden outreach clinics already established in Maine, New York, and … Cyprus?

“We go to Cyprus every year — for 37 years now,” Kirk said of a connection the organization made long ago with the Mediterranean island. “We’ll see 300 kids in four days of the clinic, and over the course of a year, 10 to 20 will come to Springfield and stay in the Ronald McDonald House here while they receive care — typically surgical care.

“We’ve had an ancient telehealth connection with Cyprus, and we’re now updating that to the latest technology, so we can have telehealth clinics with Cyprus four to six times a year in addition to going over there,” he went on. So we’re going to focus on taking care of more kids.”

That is, after all, the core of the Shriners mission.

Comments are closed.