Winning Proposition – Grant Establishes Adaptive Sports Program for Disabled Veterans

Susan Teitel is a disabled veteran, but you’d never know it. Even though she has plates in her neck, and is “held together by screws,” as a result of injuries she sustained when she was hit by a military bus while serving in the Army in Europe, she is a golf pro and an active member of the LPGA’s Teaching and Club Professional Division since 1992.

Her swing may be a bit different — it’s a compacted, yet controlled model but it allows her to not only play well, but also instruct others on the fundamentals of the game. However, she said it’s her experience with her disability that makes her a knowledgeable, compassionate, and effective teacher, especially for those with their own disabilities.

This personal awareness and empathy that have proven so useful to Teitel for the past several years will be invaluable as she participates as an instructor in a new program funded by a one-year, $25,000 grant that has been awarded to the Springfield-based Center for Human Development (CHD) Disability Resources. That agency’s mission is to empower those who have physical disabilities or visual impairments by offering activities like adaptive sports and recreational outings that are hard for disabled players to find, due to a lack of team organization and expensive adaptive equipment that is necessary to play a variety of sports.

The grant, provided by the U.S. Department of Veterans Affairs (VA) and the U.S. Olympic Committee in support of Paralympic sports and physical-activity programs for disabled veterans, is administered through New Hampshire-based AbilityPLUS Adaptive Sports.

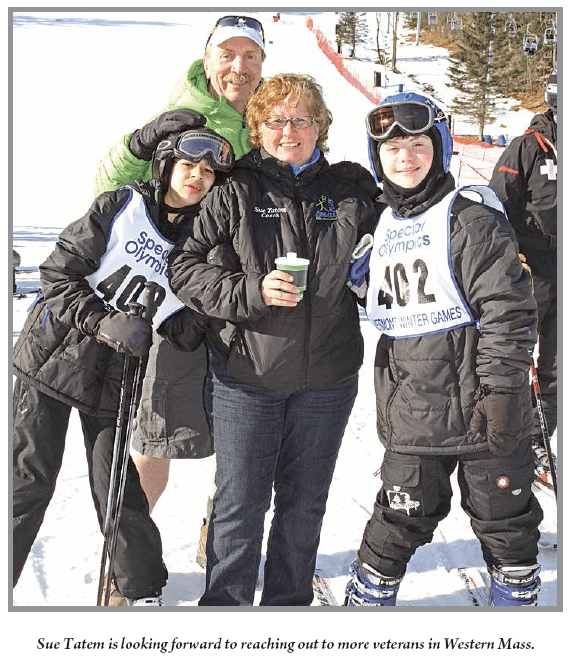

Sue Tatem, executive director of the AbilityPLUS program for the past eight years, operates out of Mt. Snow, Vt., and wrote the grant application with CHD Disability Resources and its energetic program director, Nancy Bazanchuk, specifically in mind.

Bazanchuk, one of BusinessWest magazine’s 40 Under Forty honorees in 2010, was born with a congenital ,condition that required amputation of both her legs above the knee. Running the CHD program for the past 16 years, she knows what adaptive equipment is needed for sports of all seasons, and has worked with Tatem on numerous adaptive skiing programs in recent years.

The grant, Tatem explained, covers a specific program for injured service people called Soldiers for Soldiers. It is designed to promote independence and quality of life for veterans who incurred life changing injury as a result of their service, and to foster the most successful, well-adjusted generation of wounded service members in the nation’s history.

Over two weekends, the Soldiers for Soldiers program will allow two sets of 20 to 25 veterans to participate in three days of events, during which they will experience a variety of sports using equipment that is adapted to their injuries — or, in the case of post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD), discover a way to belong on a team and consider reaching physical and mental goals.

A July weekend with lodging and transportation will include golf, sled hockey, and biking, and an August weekend will consist of rowing, kayaking, waterskiing, and another activities that may be tailored to the types of disabilities that the participants have.

But the grant also gives CHD an important designation: it will name CHD as a Paralympic sport club, one that has very strong ties to the adaptive version of the Olympics, the Paralympic Games (more on this later). CHD is the newest of 25 such organizations in New England, and is thus connected to a network of more than 150 Paralympic communities nationwide.

Usually, said Bazanchuk, skilled disabled athletes get noticed by Paralympic coaches through the structure of a Paralympic sport club.

“AbilityPLUS is also a Paralympic sport club, so any program that we put on together is a Paralympic experience,” added Tatem, who will have to reapply for another grant next year, but the hope is that the program can become self-sustaining. “Once we host an event like this, we can go out and look for funding. It gives us all an opportunity for growth and advancement as adaptive specialists, as well as the backing of the Paralympics financing, coaching, motivation, and so many other areas.”

Bazanchuk is not only excited about the additional awareness opportunities for Paralympic athletes, but echoes Tatem about the new grant-funding possibilities that the Paralympic Committee offers. “Right now, their major funder is the VA,” she said, adding that the VA has access to considerably more

funds than a typical sponsor.

And she would know. Bazanchuk’s daily challenge is determining where new funding will come from for all her adaptive sports programs, and with federal grant possibilities, this newly formed team has much to cheer about.

This month, HCN takes an in-depth look at CHD’s new federal designation and the special veterans program that will offer as many new opportunities to its administrators as it will to those injured service members who are determined not to let their disabilities limit their choices — or their quality of life.

Level Playing Field

Referring to the U.S. Paralympic organization’s website, Bazanchuk told HCN that the Paralympic Games derives its name from the parallel scheduling of the competition for disabled athletes with the Olympic Games. Since the 1988 Summer Games in Seoul, South Korea, the summer and winter Paralympic Games are held immediately following the respective Olympic Games and involve hundreds of athletes with a range of physical and intellectual disabilities, including mobility issues, amputations, blindness, and cerebral palsy.

According to the Paralympics website, there are many categories in which athletes compete, and the disabilities are broken down into six broad categories, including amputee, cerebral palsy, intellectual disability, wheelchair, visually impaired, and ‘Les Autres’ (all other disabilities, like dwarfism, multiple sclerosis, and congenital disorders).

Because of Bazanchuk’s disability, she considers herself not only an ‘adaptive specialist,’ but also an expert in disability awareness. Her disability didn’t stop her from becoming a varsity swimmer in high school or competing in the pool while attending Bridgewater State University. After college, she said, there were no other forums in which to compete — so she set about creating some.

Now that she manages a host of adaptive sports programs at CHD Disability Resources for others with disabilities from moderate to severe, both physical and visual — she and Tatem know that many young people and disabled veterans may be overlooked and not have any other chances to prove themselves when it comes to inclusion on Paralympics teams.

But not all disabled athletes are going to rise to the Paralympics level; many will be simply seizing an opportunity to compete and experience the many rewards that come with such opportunities, said Tatem.

She knew that, in order to create more of these life-altering experiences, she’d have to move beyond the ski slopes to other seasonal sports, such as golf, outdoor basketball, kayaking, waterskiing, and others, and Bazanchuk’s established programs will allow her to reach more veterans than she could in New Hampshire and Vermont.

“Now, it means I can access some of her resources in the Springfield area, as well as the VA in Northampton and Albany, and there are potentially more injured service members that we can attract by sheer population numbers alone.”

It is evident to Teitel and Tatem that the VA is now paying more attention to wounded soldiers coming back from recent conflicts, as well as those older injured veterans who seem to have been forgotten.

“Coming from a military background with a brother that served in Iraq, I think the VA has come to realize that they absolutely need to do more for injured service members and veterans,” said Tatem.

She went on to note that the VA is now supporting sports and recreational programming, like the Paralympics and AbilityPLUS, that will continue veterans’ therapy, in whatever form they’ve been treated, ,and improve the quality of life for not just the men and women who are coming back now, but for those that have been back for some time.

At CHD Disability Resources, Bazanchuk has presided over an expansion that has fostered exponential growth in athlete participation, from 69 individuals in 1997 to more than 800 currently, ranging in age from 3 to 97. Her main goal for all participants in her CHD programs is simply to be considered a member of whatever team they are playing on. Due to the grant and Paralympic designation, CHD Disability Resources is now better positioned than ever to support injured service people and kids, but there are still obstacles to overcome, she said.

Going the Distance

For veterans to participate in the Soldiers for Soldiers weekends, they must know about it, said Bazanchuk, who will be dropping off brochures at local veterans services facilities to get the word out. And with limited funding, she will have to be creative.

Teitel has done the same in the past. She started her adaptive GAP (Golf for All People) program through basic grassroots outreach. Knocking on the doors of local physical-therapy and rehabilitation centers in the area, she offered her program to physical and occupational therapists as an additional outdoor therapeutic channel for their patients.

“It’s really difficult in the Northeast to connect with the injured service members because we don’t have any active bases here,” she explained, adding that some recruitment of the activeduty injured can be reached at reserve bases like Westover.

But through the VA and other agencies that serve veterans, Teitel believes Bazanchuk can effectively recruit participants. “Not everybody is on Facebook or knows where to research programs like Paralympics, so I think Nancy is moving in the right direction.”

And she should know. When Teitel began the GAP program, the participants’ extreme disabilities surprised her. “It wasn’t just some people who used to play golf who were injured an put their clubs away; it was people who had all kinds of severe disabilities that had never played golf.”

That experience opened her eyes to the power of suggestion and the need for an athletic outlet, but thankfully Teitel’s equipment needs were and are less challenging than other sports. The grant application that Tatem wrote is very specific and fills administrative needs, like participants’ lodging, but also specific requirements like tandem bicycles, adaptive kayaks, extra equipment for sled hockey, and sports wheelchairs.

Tatem said that $25,000 will not cover all the equipment and transportation- related costs. And the logistical issues involved with getting participants to the events will have to be rectified before the summer, because there are many challenges. For instance, sports wheelchairs don’t collapse the way a traditional wheelchair does, so fitting them in a van or other carrier is an issue.

“We can get equipment, but you can’t throw one of the hand cycles up on a bike rack on top of your car — it’s not made for it,” said Tatem. “So transportation, not just for us, but for our equipment, is a challenge.”

Communication and transportation issues are just another set of hurdles that organizers of the Soldiers for Soldiers program believe can be overcome, especially now that they have additional funding and awareness power through the new grant and Paralympic designation. And all those involved will continue to provide adaptive athletic programs that will help those veterans and others with disabilities to realize life-changing experiences, even when they feel it’s a long shot that can never be achieved.

“Sports offers everybody a way to connect and helps people realize they are part of a bigger community,” added Bazanchuk. “These vets, for that hour or two hours they are playing sports, they’re just athletes … and at the end of the day, that’s what it’s all about.”

Comments are closed.